Archive for the ‘Quotations’ Category

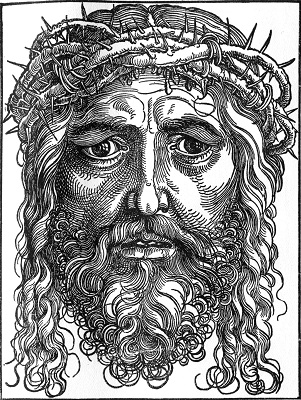

Sacrilege

The Judeo-Christian ethic of charity derives from the assertion that human beings are made in the image of God, that is, that reverence is owed to human beings simply as such, and also that their misery or neglect or destruction is not, for God, a matter of indifference, or of merely compassionate interest, but is something in the nature of sacrilege. — Marilynne Robinson, The Death of Adam, 47-48

Worship is the foundation of righteousness

The first foundation of righteousness undoubtedly is the worship of God. When it is subverted, all the other parts of righteousness, like a building rent asunder, and in ruins, are racked and scattered. What kind of righteousness do you call it, not to commit theft and rapine, if you, in the meantime, with impious sacrilege, rob God of his glory? or not to defile your body with fornication, if you profane his holy name with blasphemy? or not to take away the life of man, if you strive to cut off and destroy the remembrance of God? It is vain, therefore, to talk of righteousness apart from religion. Such righteousness has no more beauty than the trunk of a body deprived of its head. Nor is religion the principal part merely: it is the very soul by which the whole lives and breathes. Without the fear of God, men do not even observe justice and charity among themselves. We say, then, that the worship of God is the beginning and foundation of righteousness; and that wherever it is wanting, any degree of equity, or continence, or temperance, existing among men themselves, is empty and frivolous in the sight of God. We call it the source and soul of righteousness, in as much as men learn to live together temperately, and without injury, when they revere God as the judge of right and wrong. — Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, book 2, chapter 8, section 11

Mountain and sea

Mark 11:22-25 is a well-known passage on faith:

Mark 11:22-25 is a well-known passage on faith:

And Jesus answered them, “Have faith in God. Truly, I say to you, whoever says to this mountain, ‘Be taken up and thrown into the sea,’ and does not doubt in his heart, but believes that what he says will come to pass, it will be done for him. Therefore I tell you, whatever you ask in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours. And whenever you stand praying, forgive, if you have anything against anyone, so that your Father also who is in heaven may forgive you your trespasses.”

In his commentary on the gospel of Mark, Mark Horne writes about this and the context:

The fig tree story is sandwiched around the story of Jesus’ “cleansing” of the Temple (as it is commonly called). The miracle of the withered fig tree is a parable for Jerusalem and the people of Israel. God wants some fruit from them and he is about to judge them because they are not producing any.

Thus, Jesus’ discussion of prayer in Mark 11:22-26 is not simply a timeless exhortation to have faith and know that all prayers asked in faith will be answered. Jesus is discussing the prayers which the early Church will have to pray in the face of opposition from the Temple Mount. . . . Jesus is not speaking of mountains in general. He has made a point of saying which mountain will be cast into the sea by believing prayer. The “sea” in this case is the same sea Daniel saw in his vision (Dan. 7; cf. Rev. 17:15). Speaking of a foreign invasion as a drowning flood was not uncommon rhetoric for a prophet (Is. 8:7; Jer. 47:2). . . . It is the Gentile nations who will overwhelm Jerusalem as a flood and trample the city underfoot. Just as Jesus cursed the fig tree, so will God deliver the Church through the prayers of the saints.

For this reason, it is important that the persecuted saints not become personally vindictive and hateful. Jesus warns them to forgive all personal offenses. . . (149-150)

Even before Daniel, Isaiah and Jeremiah, we see mountains battling with the sea in Psalm 46:

God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble. Therefore we will not fear though the earth gives way, though the mountains be moved into the heart of the sea, though its waters roar and foam, though the mountains tremble at its swelling. There is a river whose streams make glad the city of God, the holy habitation of the Most High. God is in the midst of her; she shall not be moved; God will help her when morning dawns. The nations rage, the kingdoms totter; he utters his voice, the earth melts. The LORD of hosts is with us; the God of Jacob is our fortress. . . .

Because of Israel’s faithlessness, the city of God was cast into the Babylonian sea in the time of Nebuchadnezzar, but was re-established by God through Cyrus. Antiochus Epiphanes later covered the mountain with the Greek sea. And Jerusalem would be finally cast into the Roman sea in A.D. 70. We see a hint in each case that it is because of the prayers of the persecuted and oppressed that the corrupt and unrepentant mountain is cast into the sea.

Psalm 46 gives hope — not that the sea would be kept at bay, but that there would be protection and restoration for the persecuted, for the faithful and repentant remnant, even though the mountain is destroyed. Just as he had previously desolated the temple (e.g., Ezek. 10), Jesus left the temple desolate of his presence (Mark 13), so that he was no longer “in the midst of her.” He established a new city-mountain in his church (Heb. 12:18ff).

I wonder if there is a subtle ambiguity to this prophetic imagery. For those who do not repent, the raging sea destroys the mountain. But for those who are faithful to Jesus, Jew and Gentile are united in a different and life-giving way, so that in Jesus the two become one tree (Rom. 11), one man and body (Eph.). Both are accomplished through the prayer and witness of the church.

Realizing the pointed nature of Jesus’s imagery here does not lessen the application of this passage to our faith today; on the contrary, it underscores the great power of the praying church.

Christocracy

David Field gives a fantastic summary of the notion of a confessionally Christian government in his paper, Samuel Rutherford and the Confessionally Christian State (PDF).

David Field gives a fantastic summary of the notion of a confessionally Christian government in his paper, Samuel Rutherford and the Confessionally Christian State (PDF).

Field asserts a postmillennial perspective, then adds a startling historical observation:

It took 1400 years for 1% of the world’s population to become Christians and then another 360 years for that to double to 2%. Another 170 years saw that grow from 2% to 4% and then, between 1960 and 1990 the proportion of the world’s population made up of Bible-believing Christians rose from 4% to 8%. Now, in 2007, one third of the world’s population confesses that Jesus is Lord and 11% of the world’s population are “evangelical” Christians. The evangelical church is growing twice as fast as Islam and three times as fast as the world’s population. South America is turning Protestant faster than Continental Europe did in the sixteenth century. South Koreans reckon that they can evangelize the whole of North Korea within five years once that country opens up. And then there’s the Chinese church consisting of tens of millions of Christians who have learned to pray, who have confidence in Scripture, who know about spiritual warfare, have been schooled in suffering and are qualified to rule. One day in the next century that Church — tens of millions of Christians trained to die — will be released into global mission and our prayers for the fall of Islam will be answered.

Field then lays out Samuel Rutherford’s vision for Christian constitutional government, and defends it against a number of common objections, concluding that:

Given the purpose, origin, nature, and stuff of the human person, it is clear and important that each human being confess the triune God, recognize Jesus as Lord, and live with the Word of God as his or her supreme authority. To Rutherford and the covenanting tradition, it is no less clear and important, given the purpose, origin, nature, and stuff of human government that each human ruler also confess the triune God, recognize Jesus as Lord, and live with the Word of God as his or her supreme authority.

If you find Field’s essay provocative, here’s some additional reading to consider:

- Abraham Kuyper’s Stone lectures on Calvinism were my first introduction to this viewpoint: the insistence that the nations exist for God, and that the magistrate has a duty to God, whether or not he acknowledges it.

- John Frame lays out some helpful principles in his article, Toward a theology of the state

- Peter Leithart discusses many aspects of a Christian attitude towards the state in his books, Against Christianity, Defending Constantine, and Between Babel and Beast.

- Kuyper introduced the notion of sphere sovereignty, which wrestles with the complementary ways that Jesus’s lordship is expressed in different spheres of life such as the church, family and state. David Koyzis describes how this was developed and advanced by students of Kuyper such as Herman Dooyeweerd.

Hat tip: Uri Brito

Noah

In these articles from 1990 and 1991, James Jordan writes on the meaning of the Noahic covenant and its application today:

In these articles from 1990 and 1991, James Jordan writes on the meaning of the Noahic covenant and its application today:

A quote:

When the Church is faithful, God will convert the heart of the ruler and he will rule righteously. Conversely, when the ruler is evil and destructive, this means that the Church has not been pleasing to God. The Church is always in charge of culture, and she has been in charge ever since the Flood. We don’t have to take the world and culture over. We already have them. We just have to start using them aright. . . . We don’t change our [rulers] by hypocritically telling them to do things we don’t do. That is the problem with Christian activism and evangelism today. We go door to door telling people they should fear God, when we don’t fear Him enough to do what He says. We tell the government to judge justly, when we refuse to execute justice in Church discipline. We want the government to get out of debt, when the Church owes trillions of dollars in back tithes to God.

Sweeter than honey

My pastors are preaching through Jesus’s sermon on the mount. It’s refreshing to be reminded of the rightful place of God’s law in the Christian life. Sometimes it is easy for us to dismiss the place of law for the Christian; after all, we are not under law, but under grace. And since the law cannot save us, is there any use for it other than to condemn us and drive our miserable souls to Jesus?

My pastors are preaching through Jesus’s sermon on the mount. It’s refreshing to be reminded of the rightful place of God’s law in the Christian life. Sometimes it is easy for us to dismiss the place of law for the Christian; after all, we are not under law, but under grace. And since the law cannot save us, is there any use for it other than to condemn us and drive our miserable souls to Jesus?

If we were to stop there, the godly sentiments of Psalm 119 are left sounding completely foreign to us. How then are we to understand the law as a source of blessing and delight?

Protestants have historically recognized three uses of the law: to restrain our wickedness, to reveal sin, and to direct and guide the lives of Christians. We might say that this third use, often called the “rule of life,” is to be led in the pleasant “paths of righteousness.” It is in this way that the law brings us life and joy rather than condemnation. And in fact God always intended for his people to relate to his law this way. We can see this in the very giving of the law: he introduces it by emphasizing that “I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery” (Exodus 20). Israel was to obey God as those who were already saved, whom God had already chosen to dwell among — not as those who were trying to earn God’s favor and salvation in the first place. It is true that God is holy, that none of us is without sin, and we cannot approach him without suffering the curse of the law. But God knows our frame; he understood that we would sin. He made temporary provision for sins in the sacrificial system, and made permanent provision for our sins in Jesus, who became a curse for us.

Judicially the law does accuse us, and we must deal judicially with the law through Jesus or else suffer condemnation and wrath. But as Trinitarians we know that there are always complementary facets. Relationally God’s people deal with the law as those who are adopted sons. God is the father who puts a dollar in our grubby little hands to buy him a birthday present, and then delights in our present! Calvin puts it this way:

When God is reconciled to us, there is no reason to fear that he will reject us, because we are not perfect; for though our works be sprinkled with many spots, they will be acceptable to him, and though we labour under many defects, we shall yet be approved by him. How so? Because he will spare us; for a father is indulgent to his children, and though he may see a blemish in the body of his son, he will not yet cast him out of his house; nay, though he may have a son lame, or squint-eyed, or singular for any other defect, he will yet pity him, and will not cease to love him: so also is the case with respect to God, who, when he adopts us as his children, will forgive our sins. And as a father is pleased with every small attention when he sees his son submissive, and does not require from him what he requires from a servant; so God acts; he repudiates not our obedience, however defective it may be.

Because the law comes to us from a wise and loving father, a wise and good king and shepherd, and a life-giving helper, we ought to count it as a delight — and we can be confident that patient trust and persistent obedience will bring us true blessing. And because we are sons, we ought also to be growing in the law, seeking to imitate our father by meditating on his law and obeying it.

The fact that law is instruction from our father means that it helps to make us wise and mature. That should come as no surprise: Solomon, who excelled all the kings of the earth in wisdom, gave us the book of Proverbs, which is itself an extended meditation on the ten commandments. Consider: it comes to us in the context of the fifth commandment (“my son”), and teaches us about the fourth commandment (work), the sixth commandment (anger), the seventh commandment (the forbidden woman), and others. Jesus, the one greater than Solomon, does exactly the same in the sermon on the mount, drawing wisdom from God’s law (“you have heard”) to teach us how we ought to tend the soil of our hearts and to warn us of the ensnaring and hardening effects of sin.

Paul speaks similarly of maturity in Galatians 4. The law is a guardian or tutor, under which we are indistinguishable from slaves. But in Jesus the Son we receive adoption as sons; we are no longer under the tutor but are heirs come into our inheritance. And yet clearly this does not mean we should put our tutor and lessons out of mind. True, there are some parts of our discipline and training (e.g., dietary laws) from which we are now set free, just as a child no longer drinks from a bottle, a runner in a marathon is no longer running sprints, and a pianist on stage is no longer playing scales and etudes. But God intends that even in the freedom of sonship we live out of all of our training; and there is a great deal of the law that we must still obey and build upon with patience and persistence. In fact, God now imprints his law on our minds and hearts (Hebrews 8-10).

Since we now deal with the law relationally, our obedience is not a matter of earning and keeping God’s favor but is a matter of loyalty and allegiance to God. And so the law may sober us but it cannot terrify us. In fact, we must follow the pattern of David, Solomon and Jesus: we should train ourselves to think of God’s expectations for his sons as a delight, as the path of blessing and protection; and we should labor to grow in wisdom and maturity through studying God’s law, meditating on it and disciplining ourselves to obey it.

All that is gold does not glitter

I was trying to articulate recently to a friend why I so deeply love the over-arching savor of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. I started to say that it was a world in which God was sovereign, but that doesn’t quite capture it.

I was trying to articulate recently to a friend why I so deeply love the over-arching savor of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. I started to say that it was a world in which God was sovereign, but that doesn’t quite capture it.

Mark Horne has recently been posting on Proverbs and wisdom, and quoted Bilbo’s riddle of Strider:

All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.From the ashes a fire shall be woken,

A light from the shadows shall spring;

Renewed shall be blade that was broken,

The crownless again shall be king.

This made me think: Middle-earth is a world in which Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and the Song of Solomon are all true. It is a creation subjected to futility, unwillingly, but in hope, with an end of maturity and glory. Patience, waiting, longing, work and groaning are all required; and there is a bittersweetness to most joy and victory, because life comes through sacrifice and death. Tolkien does an outstanding job of helping you to feel the passage of time. The length of the book, Bombadil, the scouring of the Shire — it is all necessary in this light.

Tolkien writes of a story’s having a “glimpse of Truth.” Death and life themselves in Middle-earth have the savor of God’s world.

Examine

And [David] said, “Is there not still someone of the house of Saul, that I may show the kindness of God to him?” Ziba said to the king, “There is still a son of Jonathan; he is crippled in his feet.” The king said to him, “Where is he?” And Ziba said to the king, “He is in the house of Machir the son of Ammiel, at Lo-debar.” Then King David sent and brought him from the house of Machir the son of Ammiel, at Lo-debar. And Mephibosheth the son of Jonathan, son of Saul, came to David and fell on his face and paid homage. And David said, “Mephibosheth!” And he answered, “Behold, I am your servant.” And David said to him, “Do not fear, for I will show you kindness for the sake of your father Jonathan, and I will restore to you all the land of Saul your father, and you shall eat at my table always.” And he paid homage and said, “What is your servant, that you should show regard for a dead dog such as I?” Then the king called Ziba, Saul’s servant, and said to him, “All that belonged to Saul and to all his house I have given to your master’s grandson. And you and your sons and your servants shall till the land for him and shall bring in the produce, that your master’s grandson may have bread to eat. But Mephibosheth your master’s grandson shall always eat at my table.” . . . So Mephibosheth ate at David’s table, like one of the king’s sons. — 2 Samuel 9:3-11

Here’s a thought experiment. Imagine David saying to Mephibosheth: “You must eat at my table in a worthy manner.” Does David mean that:

- Mephibosheth should approach David at every meal, confessing “What is your servant, that you should show regard for a dead dog such as I?” Or that

- Mephibosheth should eat each meal with joy and congenial fellowship befitting the king’s sons.

We know that Mephibosheth never forgot he was undeserving of David’s favor, and continued to approach David with appropriate humility, respect and love (2 Samuel 19:24-30). But this is not incompatible with Mephibosheth’s living in the good of David’s favor. This is a meal, after all: my answer is #2. David made Mephibosheth his son and would have expected him to behave as a son.

We are as undeserving of God’s favor as Mephibosheth and the prodigal son. And yet in Jesus we do receive God’s favor; we been made not merely servants, but beloved sons and fellow heirs. Both David and the prodigal father are types of our Father in heaven, who by his grace now names us not sinners but saints. This shapes even our fear of the Lord: we fear the Lord not as impostors hanging by a thread, but as sons who have a responsibility to be loyal. He has made it fitting for us to approach his table as sons: he has given us the proper attire (Matthew 22:1-13) and has made his feasts a time of joy and not sorrow (Nehemiah 8:9-12).

Obviously I have 1 Corinthians 11 in mind in this thought experiment. There, Paul commands us (1) not to eat of the Lord’s supper unworthily, (2) to examine ourselves, and (3) to discern the body. It is common to read Paul as saying that (1) our sin — whether in general or only unconfessed — is what makes us unworthy for the supper; (2) therefore we examine ourselves and confess sin, (3) discerning that Jesus’s own body and blood offered on the cross are our only hope. Is this what Paul is saying? This is roughly the interpretation that Calvin, the Westminster catechisms, and others take. But it is to say the opposite of what I concluded in my thought experiment above, and to make the Lord’s supper into something different from a family meal.

Certainly we should not approach the table with unconfessed sin, or lacking appreciation for God’s great mercy to us. But there is a better way of understanding Paul’s warnings. Throughout 1 Corinthians, Paul is concerned for unity in the church. Beginning in chapter 10, he names the church as the body of Christ, and he continues without interruption to emphasize the unity, interconnectedness and interdependency of the body through chapter 12. In this context, his overwhelming concern for their practice of the Lord’s supper (chapters 10-11) is that it must reflect their unity and love as the body of Christ. Reading Paul’s warnings in light of all this, it becomes clear that (1) to eat unworthily is actually to eat without consideration of one another; (2) we therefore examine ourselves to ensure we are including, loving, preferring one another; and (3) we do this because we discern that we are Christ’s body, and Christ’s body is not divided. Considering this, and considering Mephibosheth and the prodigal son, we should not eat the Lord’s supper reservedly, but joyfully, as fellow sons and daughters.

Wayne Grudem concludes this as well. In Systematic Theology, he writes:

In the context of 1 Corinthians 11 Paul is rebuking the Corinthians for their selfish and inconsiderate conduct when they come together as a church: “When you meet together, it is not the Lord’s supper that you eat. For in eating, each one goes ahead with his own meal, and one is hungry and another is drunk” (1 Cor. 11:20-21). This helps us understand what Paul means when he talks about those who eat and drink “without discerning the body” (1 Cor. 11:29). The problem at Corinth was not a failure to understand that the bread and cup represented the body and blood of the Lord — they certainly knew that. The problem rather was their selfish, inconsiderate conduct toward each other while they were at the Lord’s table. They were not understanding or “discerning” the true nature of the church as one body. This interpretation of “without discerning the body” is supported by Paul’s mention of the church as the body of Christ just a bit earlier, in 1 Corinthians 10:17: “Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of one bread.” So the phrase “not discerning the body” means “not understanding the unity and interdependence of people in the church, which is the body of Christ.” It means not taking thought for our brothers and sisters when we come to the Lord’s Supper, at which we ought to reflect his character.

What does it mean, then, to eat or drink “in an unworthy manner” (1 Cor. 11:27)? We might at first think the words apply rather narrowly and pertain only to the way we conduct ourselves when we actually eat and drink the bread and wine. But when Paul explains that unworthy participation involves “not discerning the body,” he indicates that we are to take thought for all of our relationships within the body of Christ: are we acting in ways that vividly portray not the unity of the one bread and one body, but disunity? Are we conducting ourselves in ways that proclaim not the self-giving sacrifice of our Lord, but enmity and selfishness? In a broad sense, then, “Let a man examine himself” means that we ought to ask whether our relationships in the body of Christ are in fact reflecting the character of the Lord whom we meet there and whom we represent. (997)

Grudem goes on to cite Matthew 5:23-24 as an example of making relationships right before coming to worship.

God could have chosen for this sacrament to take any form. It is highly instructive that he chose for it to take the form of a meal, with all the rich imagery that carries. He intends for us to enjoy it in fellowship with him and one another.

Seed

Tolkien, on p. 855 of The Lord of the Rings:

Tolkien, on p. 855 of The Lord of the Rings:

‘That is a fair lord and a great captain of men,’ said Legolas. ‘If Gondor has such men still in these days of fading, great must have been its glory in the days of its rising.’

‘And doubtless the good stone-work is the older and was wrought in the first building,’ said Gimli. ‘It is ever so with the things that Men begin: there is a frost in Spring, or a blight in Summer, and they fail of their promise.’

‘Yet seldom do they fail of their seed,’ said Legolas. ‘And that will lie in the dust and rot to spring up again in times and places unlooked-for. The deeds of Men will outlast us, Gimli.’

‘And yet come to naught in the end but might-have-beens, I guess,’ said the Dwarf.

‘To that the Elves know not the answer,’ said Legolas.

I don’t know whether there is one true Roman Catholic eschatology or what it might be. Tolkien at least had a pessimistic eschatology which he thought was a necessary part of his Roman Catholicism. And as much as the fall of Sauron was an epic victory, this pessimism shades his work as well. But the above is a wise and I think true observation regardless of one’s eschatology. Death and resurrection is a pervasive and inescapable motif in life and creation.

Whether for civilization, church or family, better the deaths should be ones of repentance and self-sacrifice than of reaping and judgment.

Eat

Two years ago I wrote “They preach,” of the Lord’s supper, but it could be improved by turning the comparison on its head. Fellowship over a meal is a much clearer picture of how God relates to his people than preaching, so that preaching is itself a bit of both setting out the feast and also table talk (John 21), and evangelism is an invitation to the feast (Luke 14, Revelation 19). The Lord’s supper is not merely a picture of how God relates to us, but one of the ways that he actually, presently relates to us. It is the family meal, and we eat it in fellowship with him.

Two years ago I wrote “They preach,” of the Lord’s supper, but it could be improved by turning the comparison on its head. Fellowship over a meal is a much clearer picture of how God relates to his people than preaching, so that preaching is itself a bit of both setting out the feast and also table talk (John 21), and evangelism is an invitation to the feast (Luke 14, Revelation 19). The Lord’s supper is not merely a picture of how God relates to us, but one of the ways that he actually, presently relates to us. It is the family meal, and we eat it in fellowship with him.

Even in Genesis 2 Moses makes much of the fact that God provided Adam and Eve with food to eat. Adam’s sin involved eating, and God’s curse after the fall meant not only that fellowship with God was broken, but also that eating would require pain and toil (Genesis 3). As God’s plan of redemption unfolds in his covenants with man, food and table fellowship are not far, so that we often speak of a covenant meal.

God gave Adam the plants of the field, and to Noah he added living things (Genesis 9): God’s covenants keep getting better! Melchizedek, who we know is a type of Christ, set before Abram a meal of bread and wine (Genesis 14). Later Abraham prepared a meal for the three strangers who visit him (Genesis 18).

The Mosaic covenant is full of covenant meals. Passover commemorates God’s deliverance from Egypt, and Israel was commanded to celebrate it throughout their generations (Exodus 12). God provided water, meat and daily bread for Israel in the wilderness; both the bread and the rock that gave the water are types of Christ. Through Moses God also established Sabbath days and years for feasting and refreshment, and a calendar of other covenant feasts throughout the year. These holy feasts were such times of rejoicing before God that grief and weeping in conviction over sin was to be put aside (Nehemiah 8). Even tithing seems to have been not simply handing things over to the Levites, but also feasting with them before God (Deuteronomy 14). “Whatever you desire” — oxen, sheep, wine, beer. Finally, sacrifices regularly involved the priests’ eating the sacrifice, and sometimes the worshipper’s eating as well (Leviticus 7, 1 Chronicles 16). Covenant meals and feasts are not merely gifts from God, but a real part of regular fellowship with God.

Even among the covenants of men we find covenant meals. Jacob and Laban established their covenant with a meal (Genesis 31). David kept his covenant with Jonathan not simply by preserving Jonathan’s crippled son Mephibosheth, but by ensuring his food was provided for and furthermore bringing him to eat perpetually at his table (2 Samuel 9). David is certainly a type of Christ here.

Jesus was falsely accused of sin over who he shared meals with and how he ate (Luke 7). He declared that “whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life” (John 6). Many turned away at this; I wonder if they were offended not so much by the suggestion of cannibalism as by the implication of human sacrifice. John certainly intended for us to connect Jesus’s statement here to the Lord’s supper, which Jesus also explicitly relates to his sacrifice in the new covenant (Luke 14).

Feasting is a deep picture of how God relates to us. Peter Leithart has this to say about covenant meals and the Lord’s supper:

[T]he rite for animal offering ends, in most cases, with a communion meal. Priests and sometimes the worshipper receive a portion of “God’s bread” to eat. Eating together is a way to make a covenant or have fellowship. Throughout the Bible, when people conclude treaties, they eat a meal together to show that they are now friends. Jacob and Laban ate together after they had made a treaty of peace between them (Genesis 31:44-55). so also, when men draw near to God, they eat with Him. The elders of Israel eat and drink in God’s presence, and He does not stretch out His hand against them (Exodus 24:9-11). The end—the goal and the conclusion—of Israelite worship is a fellowship meal with God, and this renews the covenant. Our worship in the church is the same: After we have confessed our sins, heard God’s word, and praised Him, He invites us to His table to share a meal. We don’t eat the flesh of an animal, but the flesh and blood of the perfect sacrifice, Jesus. — A House for My Name, pp. 91-92

In a way, the old debates over “where is Christ in the Lord’s supper?” are asking the wrong question. Where are we in the Lord’s supper? We are feasting together in the presence of the one who clothes us and prepares a table before us.

God welcomes all of us to table fellowship with him, and this means we ought to welcome one another in the same way. Paul is concerned that we do not exclude one another from the Lord’s supper (1 Corinthians 10-11), and that our table fellowship does not become an occasion for despising or judging one another (Romans 14, 1 Corinthians 8-10). He even admonished Peter in this (Galatians 2).

Jesus invites and welcomes you to eat and drink at his table. Take, eat!

And Nehemiah, who was the governor, and Ezra the priest and scribe, and the Levites who taught the people said to all the people, “This day is holy to the Lord your God; do not mourn or weep.” For all the people wept as they heard the words of the Law. Then he said to them, “Go your way. Eat the fat and drink sweet wine and send portions to anyone who has nothing ready, for this day is holy to our Lord. And do not be grieved, for the joy of the Lord is your strength.” So the Levites calmed all the people, saying, “Be quiet, for this day is holy; do not be grieved.” And all the people went their way to eat and drink and to send portions and to make great rejoicing, because they had understood the words that were declared to them. — Nehemiah 8:9-12