Archive for the ‘Biblical Theology’ Category

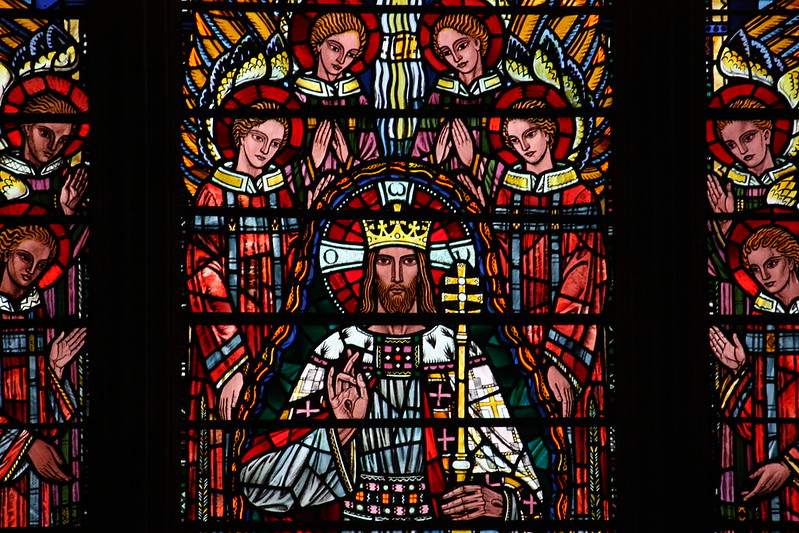

The future of Jesus

I was a long while in moving from amillennialism to postmillennialism. But like many theological watersheds, more and more I saw it everywhere, and more and more it fit with other convictions.

My friend Mark Horne argues briefly for postmillennialism in a helpful series of posts, “The future of Jesus:”

- The future of Jesus

“God’s objective in Jesus is the release of the human race from slavery — not just slavery from death but slavery from every other tyrant as well.” - Few to be saved?

“It is too small a thing to God for him to show mercy on and bring salvation to a minority of humanity.” - Are there earthly blessings to be expected in the future?

“There is our hope: Not only the return of Jesus, but the victory of His Spirit and His Gospel giving the whole world true knowledge of him and of his Word, bringing about the end of wickedness and an end to the weariness of frustrated labor.” - Will he make a difference in the world?

“If there was ever a time when God allowed human societies to exist apart from loyalty to him, that time is over. God now expects everyone to acknowledge the Lordship of His Son and to obey Him.” - So if Jesus rules, why isn’t life better?

“When the Church does not teach everything Christ has commanded we should expect him to withdraw peace and prosperity from the world. This does not disprove that he reigns and has a plan for future victory; it proves that he does.” - To three thousand-PLUS generations

“So when we read in Esther 8 about a world-wide vindication of God’s people resulting in massive proselytization ‘from India to Ethiopia,’ we should realize that that was rather minimal compared to what is to happen now that Jesus has come and died and risen again.” - The feast of booze

“Jesus loves you and your Christian family but he did not die and rise again to have you in his private party. He died and rose again not only for you but also for the whole world. He wants everyone to come to his table and he will eventually ensure that the whole world is present at his feast.” - When is Jesus king of kings?

“Jesus is not becoming king at some point in the future. To be more pointed, he is not becoming the king of all nations on earth at some point in the future. He already is.” - Who inherits the land/earth?

“How is it Christian to claim that the meek won’t inherit the earth?” - Who will kings acknowledge?

“Kings are called upon to praise the Lord. We are promised that they will all give thanks to God.” - Defending the future of Jesus

“The whole reason there is an ‘antithesis’ between God and Man is because they are claiming the same territory at the same time. The new city begins now. Or rather, began then.”

Totus Christus

Augustine spoke of the totus Christus, or the “whole Christ.” In saying this, he referred to the fact that Jesus and his church are in some ways inseparable, as husband and bride, head and body. Believers are both individually and corporately united to Jesus, and when the church is persecuted, Jesus is persecuted (Acts 9:4). He is in us and we are in him.

It is possible to stretch this imagery too far; it is a union and not an identity. And the church is utterly incomplete without Jesus, while the reverse is not true. Yet there are many applications we can draw from this.

First, this helps us to understand the doctrine of imputation. If the church is united to Jesus as body to head, then we as believers are brought into Jesus’s own obedience and death. We are actually made to be “in him” in his life and death and resurrection. Amazingly, in his death, Jesus chose to be united with us but forsaken by the Father. What love!

Second, it helps us to make some sense of Scripture’s speaking of being in Christ. Part of this is a spiritual reality. But part of it must be realized in the flesh by our participating in Christ’s church, his body. We cannot enjoy, experience and know the whole Christ if we seek to do so apart from his body the church. We must have a complete head-and-body relationship with Jesus. This also gives us a glimpse into one of the purposes of baptism. If we are baptized into Jesus (Romans 6:3), then part of that means that we are brought into his body, the church.

Third, this gives us a deeper understanding of the imagery of the Lord’s Supper. It is clear that the bread and wine represent Jesus’s body and blood. But we can understand Jesus’s body in two ways — his physical body, and his body the church. It seems that Paul has both of these senses in mind when he writes of the bread and body in 1 Corinthians 10-11. He links the one loaf of bread to the unity of Jesus’s church-body. And when he writes of “discerning the body,” I believe he is primarily concerned that we discern the body as the church, eating the Supper with love and preference for one another. We eat the Supper in a way that reflects the unity we have in the gospel. And in the following chapter, Paul elaborates even further on the image of the church as a body, emphasizing that we must walk in honor and preference and care for one another.

Third, this gives us a deeper understanding of the imagery of the Lord’s Supper. It is clear that the bread and wine represent Jesus’s body and blood. But we can understand Jesus’s body in two ways — his physical body, and his body the church. It seems that Paul has both of these senses in mind when he writes of the bread and body in 1 Corinthians 10-11. He links the one loaf of bread to the unity of Jesus’s church-body. And when he writes of “discerning the body,” I believe he is primarily concerned that we discern the body as the church, eating the Supper with love and preference for one another. We eat the Supper in a way that reflects the unity we have in the gospel. And in the following chapter, Paul elaborates even further on the image of the church as a body, emphasizing that we must walk in honor and preference and care for one another.

Finally, this reminds us that one of the ways that Jesus is with us to the end of the age (Matt 28:20) is through his church, through our shared life with one another. We enjoy his presence through his word and his Spirit, but also through his body.

Timeless theology

It seems to me that colloquial American Calvinism can tend toward a timeless theology. In our systematic theology, we tend to think primarily in terms of static eternal-eschatological realities (think TULIP) and to neglect the equally important historical-covenantal perspective. As a result, hyper-Calvinism becomes a temptation for us over against classic covenantal Calvinism (I’ve struggled with this). Similarly, the relative stasis of amillennialism becomes appealing to us over against classic postmillennial Calvinism. And when it comes to parenting, we can focus more on bringing our children to a life-defining moment of repentance and faith, rather than training them in a life of ongoing and growing repentance and faith. We have an appropriately large category for having been definitively saved, yet it seems foreign to speak in any sense of being presently saved (1 Cor 15:2). This can easily lead to a marginalization of the work of the Spirit: everything is settled, so what pressing need is there for the Spirit to wrestle with us, or for us to be drawing strength and life from the church?

It seems to me that colloquial American Calvinism can tend toward a timeless theology. In our systematic theology, we tend to think primarily in terms of static eternal-eschatological realities (think TULIP) and to neglect the equally important historical-covenantal perspective. As a result, hyper-Calvinism becomes a temptation for us over against classic covenantal Calvinism (I’ve struggled with this). Similarly, the relative stasis of amillennialism becomes appealing to us over against classic postmillennial Calvinism. And when it comes to parenting, we can focus more on bringing our children to a life-defining moment of repentance and faith, rather than training them in a life of ongoing and growing repentance and faith. We have an appropriately large category for having been definitively saved, yet it seems foreign to speak in any sense of being presently saved (1 Cor 15:2). This can easily lead to a marginalization of the work of the Spirit: everything is settled, so what pressing need is there for the Spirit to wrestle with us, or for us to be drawing strength and life from the church?

In his excellent book, The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God, D. A. Carson has this to say about the debate between Calvinists and Arminians over the doctrine of atonement, observing a creeping tendency towards hyper-Calvinism:

In recent years I have tried to read both primary and secondary sources on the doctrine of the Atonement from Calvin on. One of my most forceful impressions is that the categories of the debate gradually shift with time so as to force disjunction where a slightly different bit of question-framing would allow synthesis.

I think his observation has broader applicability for our theological formulations. We need to be sure that we are synthesizing both eternal and historical perspectives: both God’s eternal decrees and also also their covenantal working out in time and history. For some good principles on integrating perspectives like this, I recommend Vern Poythress’s book Symphonic Theology.

Cloud

Continuing my previous post’s theme of worship, I want to suggest complementary perspectives on corporate singing.

James Jordan points out that God’s glory cloud is symbolic of the society of men and angels gathered around God’s throne. What we see as a cloud in Exodus 19, 24 and Ezekiel 1 is myriads of angels in Daniel 7 and Revelation 5. He suggests that the cloud might have even consisted of angels, which you could not distinguish from a distance. In any case, there are suggestive parallels between God’s glory-cloud, his tabernacle and temple, and the true “house” of God, his people.

James Jordan points out that God’s glory cloud is symbolic of the society of men and angels gathered around God’s throne. What we see as a cloud in Exodus 19, 24 and Ezekiel 1 is myriads of angels in Daniel 7 and Revelation 5. He suggests that the cloud might have even consisted of angels, which you could not distinguish from a distance. In any case, there are suggestive parallels between God’s glory-cloud, his tabernacle and temple, and the true “house” of God, his people.

There are strong connections between singing and going to, becoming, the house of God (e.g., Ps. 22:3, 42:4, 84:4). Likewise, the angels that surround God’s throne create a glorious noise of voices and trumpets and waters and winds (e.g., Exodus 19, Ezek. 1).

Thus, in the church’s corporate singing, through Jesus our sacrifice and by the Holy Spirit, we are brought up and incorporated into the glory cloud, where we gather together with angels and with believers of all ages. We become part of God’s glorious covering as his bride, and through our singing we participate in the mighty sound of God’s presence. We announce and display his greatness and glory to all men and even to the “cosmic powers” (Eph. 6).

More than that, as a host of people and angels gathered around God’s throne, we are also an army gathered around our commander. It is no stretch to say that the church’s singing and shouting is one of the ways that we do real battle against everything that is opposed to Jesus and his church (e.g., Joshua 6; Psalm 8:2 with Matt 21:16; Acts 16:25-26).

Let us go up

Earlier this year I wrote an essay on worship as ascension.

The main idea is that our Lord’s-day corporate gathering is, symbolically, going up together to meet with Jesus in a special way. In one sense, he is with us at all times. But we are in his presence in a special way when we draw near to him in corporate worship.

The main idea is that our Lord’s-day corporate gathering is, symbolically, going up together to meet with Jesus in a special way. In one sense, he is with us at all times. But we are in his presence in a special way when we draw near to him in corporate worship.

What is the cash value of this? Three things stand out in my mind:

First, it magnifies the importance of the church gathering. We are gathering to meet with, receive from, and give to our king, and it is both a privilege and a refreshing delight to make this the highest priority of our week. We ourselves become the very house of God, he inhabits us as his house, and we meet him there in a special way. The Psalms, in particular, train us to think this way about corporate worship.

Second, it opens our eyes of faith to the greatness of what we experience in the church gathering. Perhaps you find yourself longing for the physical power and glory of Old Testament worship experiences. Why can’t we experience the same physical manifestation of God’s power and presence today? But the fulfillment is always greater than the type, and Levitical worship and temple worship were only a type of what we experience now. Formerly, only one man could approach God’s earthly throne, only once a year; and believers traveled far to eat fellowship meals in the courtyard of God’s house — but only if they were ceremonially clean. Now we are all priests, all cleansed once and for all. We all approach God’s heavenly throne weekly (in one sense), and we eat and drink regularly with Jesus at his own table inside his house. Understanding details of how our experience builds on the Old Testament types and shadows helps us to see and rejoice in how much better our experience is. This is part of the church’s maturing from guardianship to sonship. As Peter Leithart writes, the “move that the New Testament announces is not from ritual to non-ritual. . . . The movement instead is from rituals and signs of distance and exclusion . . . to signs and rituals of inclusion and incorporation.” Hebrews, in particular, trains us to think this way about corporate worship today.

Third, the weekly rhythm of going up to meet with Jesus and being sent back out into the world trains us instinctively in the Christian pattern of life. God’s forgiveness, grace, justification, acceptance, rest, and the work of the Spirit are the wellspring out of which flow our works and obedience. God has fresh mercy for us every day and every week. We receive his assurance, grace, rest and power, and are commissioned to go out into the world in his strength and power. We go out in his authority, not to earn acceptance, grace or rest, but moving out of the acceptance, grace and rest that we have already received, and with great confidence that God will continually refresh and equip us every day and every week. We receive more life, are sent out to die, and come back for more life so we can do it again and again.

It shall come to pass in the latter days that the mountain of the house of the LORD

shall be established as the highest of the mountains, and shall be lifted up above the hills;

and all the nations shall flow to it, and many peoples shall come, and say:

“Come, let us go up to the mountain of the LORD, to the house of the God of Jacob,

that he may teach us his ways and that we may walk in his paths.”

For out of Zion shall go the law, and the word of the LORD from Jerusalem.

He shall judge between the nations, and shall decide disputes for many peoples;

and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks;

nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.

— (Isaiah 2:2-4 ESV)

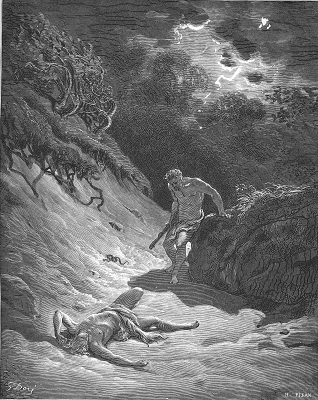

Cain

Cain would not bring a blood sacrifice to make atonement with God. Ironically, Cain required blood to appease himself.

Cain would not bring a blood sacrifice to make atonement with God. Ironically, Cain required blood to appease himself.

Thus he elevated himself to the place of God, following in the footsteps of his father. But Cain’s sin was a step beyond his father’s sin; Adam prematurely seized the mantle of judgment (which God later gives to Noah in Genesis 9:6), but Cain exercised that mantle sinfully.

Perhaps Adam was even reaping from his own sin in this. Adam’s sin resulted in the death of a son (compare Genesis 22; Leviticus 1:5, literally “son of the herd;” 2 Samuel 12; Jesus).

Pentecost

Tomorrow is Pentecost. Once, God espoused himself to his people through the letter at the first Pentecost. Now he has espoused himself to his people through his Spirit at the latter Pentecost.

Tomorrow is Pentecost. Once, God espoused himself to his people through the letter at the first Pentecost. Now he has espoused himself to his people through his Spirit at the latter Pentecost.

Be filled with the Spirit. — Ephesians 5:18

How can we obey this command?

- We pray for the Spirit (Psalm 51:10-12)

- The Spirit is the Spirit of holiness (Romans 1:4). Our sin quenches the Spirit and our receptivity to his work: so we are more filled with the Spirit when we pursue holiness and flee sin. Of course, it is only by the Spirit that we pursue holiness, but this is not a cruel irony because God is at work in our working. In other words, we are filled with the Spirit when we submit to him and to his will.

- The Spirit is the Spirit of the body (1 Cor 12:13, Eph 4:4), and the purpose of the Spirit is to build up the body (1 Cor 12:7). The Spirit is about interpersonal life and ministry. This is an extension of what theologians call the “procession” of the Spirit — the Spirit proceeds between the Father and the Son (Augustine and Edwards describe the Spirit as a sort of personified love), and proceeds to us from the Father and from the Son. But in a lesser way the Spirit also proceeds from us to one another. Because of this activity of procession and ministry in the body, the Spirit is particularly associated with corporate worship. The Spirit kindled the fire on God’s altar and now kindles a fire on us as living sacrifices. The Spirit is particularly active when we gather together before the Lord’s throne on the Lord’s day for corporate worship (Rev 1:10). Putting this together, an additional way that we can be filled with the Spirit is to persevere in being joined to the body, to allow ourselves to be ministered to by one another, and in particular to participate in corporate worship so that we are ministered to by Jesus. We go up to God’s house to meet with our husband, king and commander, and are commissioned by him to go out into the world again, freshly equipped with his Spirit.

Thanks to Anthony and John for prompting some of these thoughts. Picture from Uri Brito.

Thigh

And Jacob was left alone. And a man wrestled with him until the breaking of the day. When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he touched his hip socket, and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. Then he said, “Let me go, for the day has broken.” But Jacob said, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.” And he said to him, “What is your name?” And he said, “Jacob.” Then he said, “Your name shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed.” Then Jacob asked him, “Please tell me your name.” But he said, “Why is it that you ask my name?” And there he blessed him. So Jacob called the name of the place Peniel, saying, “For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life has been delivered.” The sun rose upon him as he passed Penuel, limping because of his hip. Therefore to this day the people of Israel do not eat the sinew of the thigh that is on the hip socket, because he touched the socket of Jacob’s hip on the sinew of the thigh. — Genesis 32:24-32

Then I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse! The one sitting on it is called Faithful and True, and in righteousness he judges and makes war. His eyes are like a flame of fire, and on his head are many diadems, and he has a name written that no one knows but himself. He is clothed in a robe dipped in blood, and the name by which he is called is The Word of God. And the armies of heaven, arrayed in fine linen, white and pure, were following him on white horses. From his mouth comes a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations, and he will rule them with a rod of iron. He will tread the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God the Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has a name written, King of kings and Lord of lords. — Revelation 19:11-16

There is a thigh touched, and a thigh inscribed. Jacob’s wound is connected with blessing, victory and dominion; Jesus’s thigh describes his authority, and the passage assures us of his victory. Jesus’s thigh and robe are connected by his name; Jacob himself is renamed, and I wonder if this is a kind of investiture. The nameless one appears in both passages, so that Jesus is not only the one with whom Jacob wrestles, but also Jacob’s antitype, Israel’s antitype.

The sun rises upon Jacob, and likewise John even goes on to describe the sun:

Then I saw an angel standing in the sun, and with a loud voice he called to all the birds that fly directly overhead, “Come, gather for the great supper of God, to eat the flesh of kings, the flesh of captains, the flesh of mighty men, the flesh of horses and their riders, and the flesh of all men, both free and slave, both small and great.” And I saw the beast and the kings of the earth with their armies gathered to make war against him who was sitting on the horse and against his army. And the beast was captured, and with it the false prophet who in its presence had done the signs by which he deceived those who had received the mark of the beast and those who worshiped its image. These two were thrown alive into the lake of fire that burns with sulfur. And the rest were slain by the sword that came from the mouth of him who was sitting on the horse, and all the birds were gorged with their flesh. — Revelation 19:17-21

I wonder if there is a connection between this and Jacob’s facing Esau as the sun rises. I have not listened to James Jordan’s lectures on Revelation yet — probably he deals with this and more. But I recall he does identify the false prophet named here with the Idumean (Edomite!) Herods. Perhaps Esau’s four hundred men are furthermore representative of Revelation’s kings of the earth; the whole earth was set against Jacob, but he overcame through patience and faith. Likewise, Jesus’s church in Revelation overcomes through persevering in patience and faith.

Life

You are not to boil a kid in the milk of its mother. — Exodus 23:19

On the principle that “it was written for our sake” (1 Cor. 9:10), James Jordan explains this law in his book, The Law of the Covenant: An Exposition of Exodus 21-23 (pp. 190-192):

It is sometimes thought that boiling a kid in milk was a magic ritual used by the Canaanites, and that this is why it was forbidden. The text, however, does not forbid boiling a kid in milk, but in its own mother’s milk. The reason is that life and death must not be mixed. That milk which had been a source of life to the kid may not be used in its death. Any other milk might be used, but not its mother’s.

This law is thrice stated in the Torah (Ex. 23:19; 34:26; Dt. 14:21). It is obviously quite important, yet its significance eludes us. There are many laws which prohibit the mixing of life and death, yet we wish to know the precise nuance of each. . .

We notice that the kid is a young goat, a child. The word only occurs 16 times in the Old Testament. In Genesis 27:9,16, Rebekah put the skins of a kid upon Jacob when she sent him to masquerade as Esau before Isaac. Here the mother helps her child (though Jacob was in his 70s at the time). In Genesis 38:17,20,23, Judah pledged to send a kid to Tamar as payment for her services as a prostitute. In the providence of God, this was symbolic, because Judah had in fact failed to provide Tamar the kid to which she was entitled: Judah’s son Shelah. Judah gave his seal and cord, and his staff, as pledges that the kid would be sent, but Tamar departed, and never received the kid. When she was found pregnant, she produced the seal and cord and the staff, as evidence that Judah was the father. The children that she bore became her kids, given her by Judah in exchange for the return of his cord and seal and his staffs. Finally, when Samson visited his wife, he took her a kid, signifying his intentions (Jud. 15:1).

These passages seem to indicate a symbolic connection between the kid and a human child, the son of a mother. (Indeed, Job 10:10 compares the process of embryonic development to the coagulation of milk.) The kid is still nursing, still taking in its mother’s milk in some sense, Jacob and Rebekah being an example of this. The mother is the protectress of the child, of the seed. This is the whole point of the theology of Judges 4 and 5, the war of the two mothers, Deborah and the mother of Sisera. Indeed, the passage calls attention to milk. The milk of the righteous woman was a tool used to crush the head of the serpent’s seed (Jud. 4:19ff; 5:24-27). How awful if the mother uses her own milk to destroy her own seed!

. . . Accordingly, one of the most horrible things imaginable is for a mother to boil and eat her own child. This is precisely what happened during the siege of Jerusalem, as Jeremiah describes it in Lamentations 4:10, “The hands of compassionate women boiled their own children; they became food for them because of the destruction of the daughter of my people.” The same thing happened during the siege of Samaria, as recorded in 2 Kings 6:28ff. In both passages, the mother is said to boil her child.

We are now in a better position to understand this law, and its placement in passages having to do with offerings to God. The bride offers children to her husband. She bears them, rears them on her milk, and presents them to her lord as her gift to him. Similarly, Israel is to present the fruits of her hands, including her children, to her Divine Husband. She is not to consume her children, her offerings, or her tithes, but present them to God. The command not to boil the kid in its own mother’s milk is a negative command; the positive injunction it implies is that we are to present our children and the works of our hands to God.

Jerusalem is the mother of the seed (Ps. 87:5; Gal. 4:26ff.). When Jerusalem crucified Jesus Christ, her Seed, she was boiling her kid in her own milk. In Revelation 17, the apostate Jerusalem has been devouring her faithful children: “And I saw the woman drunk with the blood of the saints and with the blood of the witnesses of Jesus.” Her punishment, under the Law of Equivalence, is to be devoured by the gentile kings who supported her (v. 17).

There are some obvious but also subtle ways that American culture consumes its children:

Our practice of abortion is clearly consuming our children for our own benefit. We are to sacrifice ourselves for the sake of our children, not to sacrifice our children for the sake of ourselves. Abortion is cannibalism.

Mark Horne explains that “democracy with public debt is the economic system that makes it rational for adults to eat their children.”

I wonder, though, if over a century of individualistic, conversionistic tendencies in the evangelical church have helped to enable this consuming of children. God’s own covenant name, transcending covenants old and new (Ex. 34:6-7), assures us that he intends to show mercy to our children. But the evangelical church has tended to view its infants and children as fundamentally alienated from God instead of belonging to him. We have tended to view parenting more as evangelism than discipleship; we have given our children the impression that God’s forgiveness is harder to come by, and harder to be sure of, than mommy’s and daddy’s; we have withheld from them baptism’s designation of the family name “Christian,” as well as the nourishment, joy and fellowship of the family meal, in some cases until late in their teens; we have thus taught them that God requires a sufficiently sincere and intellectual faith instead of simple trust. This has produced a very modern tendency to wish one was baptized at a later age — as though salvation depended on understanding and maturity more than faith! We teach them many songs about God’s rescuing them out of rebellion, but none about his causing them to trust in him before their birth (Ps. 22, 71, etc.). The widely applauded testimony, the one seen as particularly incisive, is that they have finally come to know God on their own terms in their late teens or in college, not that they have feared God from their youth. Thus, we have taught them to despise small beginnings, confusing conversion with the very normal experience of maturing and growth. As a result, we have led them to believe not only that they are aliens and outcasts from the kingdom, but even that they must in some ways turn and become like adults in order to enter the kingdom of heaven. While perhaps well intentioned, our fear of false assurance robs them of genuine assurance; we withhold the kingdom from those to whom it belongs, starving and quenching the work of the Spirit. And although it is true that the evangelical church has largely taught the salvation of her infants who die, yet we have almost always seen this as an unusual or exceptional work of God rather than an ordinary part of the Spirit’s work in nurturing Christian children. In short, we have taught both our children and the world that infants and children are second-class citizens of God’s kingdom, if they are citizens at all.

One of the crucial ways that the church resists abortion is in how we parent.

See also: Poythress on indifferentism and rigorism; and Leithart’s book, Against Christianity.

Far as the curse is found

In his chapter in The Glory of Kings, “Holy War Fulfilled and Transformed,” Rich Lusk deals with the unique way in which God led Israel to prosecute war in the conquest of Canaan. Lusk contrasts Israel’s conquest of Canaan against the much more restrictive demands God placed on their ordinary warfare. He goes on to establish how the conquest is typological for Jesus’s conquest of the world through the cross and the church. The church engages in battle and wrestling through our worship, prayer, sacrifice, evangelism, discipleship and ministries of mercy.

There is a kind of double meaning in the idea of something being devoted to God: it may entail either punishment or acceptance, judgment or justification. While cities were sent up in smoke as a mark of God’s judgment, the system of offerings shows a positive meaning of ascension in smoke. The penalty and judgment for sin came into play when the animal was put to death. After its death, the animal’s ascension in smoke was a positive figure of its entering into God’s presence on behalf of the worshipper. The underlying Hebrew for “whole burnt offering,” in fact, literally means “ascension offering.” Likewise, Jesus, our offering for sin, in his ascension brings us to the Father in union with him as our representative. So, today, the church wields the sword of the Spirit, the word (Eph. 6:17; Heb. 4:12), waging a campaign of devoting the world to God by spreading the fire of the Holy Spirit, life born out of repentance. Since Pentecost, we are living sacrifices.

There is a kind of double meaning in the idea of something being devoted to God: it may entail either punishment or acceptance, judgment or justification. While cities were sent up in smoke as a mark of God’s judgment, the system of offerings shows a positive meaning of ascension in smoke. The penalty and judgment for sin came into play when the animal was put to death. After its death, the animal’s ascension in smoke was a positive figure of its entering into God’s presence on behalf of the worshipper. The underlying Hebrew for “whole burnt offering,” in fact, literally means “ascension offering.” Likewise, Jesus, our offering for sin, in his ascension brings us to the Father in union with him as our representative. So, today, the church wields the sword of the Spirit, the word (Eph. 6:17; Heb. 4:12), waging a campaign of devoting the world to God by spreading the fire of the Holy Spirit, life born out of repentance. Since Pentecost, we are living sacrifices.

What struck me in thinking about this was Israel’s refusal to enter into Canaan, and how this may serve as a caution for the church. Consider Numbers 13:25-14:38. Clearly God promised to give them the land, and they saw firsthand his power to fight for them. And yet they still did not believe. Ultimately, God forgave their sin, but they had to endure the consequence of their unbelief through forty years of wandering and death. In a way, they were given only as much as they believed God for: they did not believe God could or would fight for them, so they do not enjoy the victory that God had promised.

What does this mean for the church? Jesus is the high priest whose death brings about an atoning transition from judgment to grace (Numbers 20, 35), and immediately opens the way to the gospel’s conquest of the world (Numbers 20:29-21:3). Jesus’s ascension is his coronation; the Father has now put everything in subjection under his feet (Ps. 8, Heb. 2). Here are a few ways we can work at walking in faith in Jesus’s lordship:

- Jesus is lord of nations, kings and magistrates, so our responsibility as citizens does not stop at voting and prayer: we call them to account to Jesus and seek to disciple them

- Our children belong to Jesus and his Spirit is at work in them, so our parenting owes as much to the pattern of discipleship as to evangelism

- Jesus is lord of our work, so we can work in any lawful vocation “as for the Lord,” knowing that he is beginning a new work of subduing the earth regardless of the seeming futility we see on our own time horizons

- Jesus is lord of all, so we can confidently appeal to unbelievers on the basis that they live under his rule in his realm, that everything they enjoy is a blessing from him, and that true joy and blessing is to be found in welcoming him and his lordship rather than despising him.

And belt out some Christmas songs this holiday season. Joy to the world!