Archive for the ‘Books’ Category

Years in books

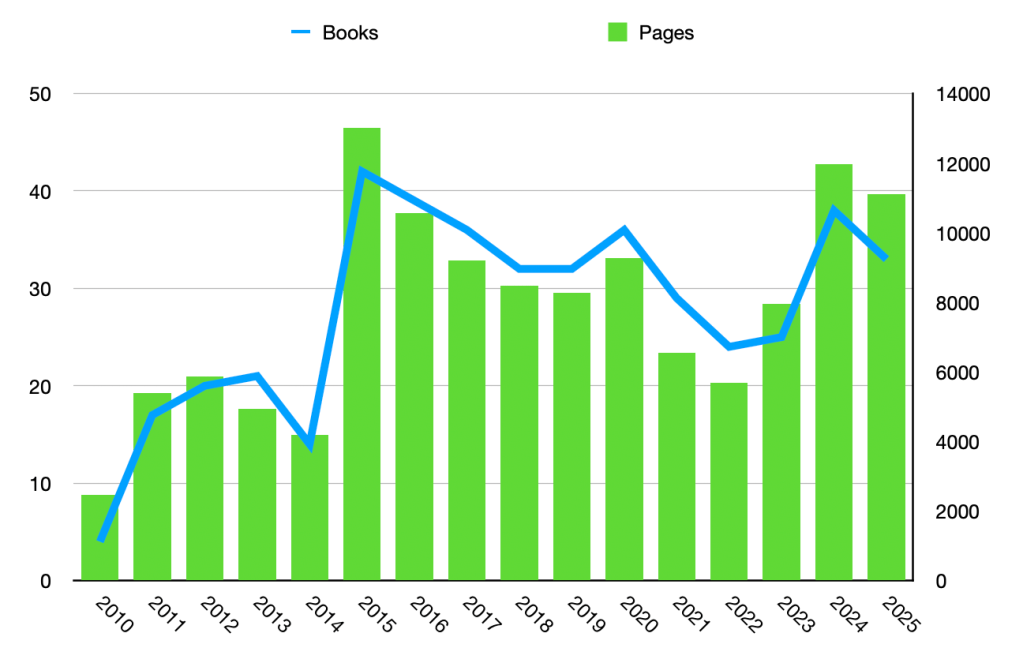

I usually feel like I have little time to read, but my Goodreads “year in books” report at the end of every year consistently surprises me. In recent years I have increased my audio book consumption. This has redoubled in the last couple of years as I traded more podcast time for book time during my commute to work, and also as our family read-aloud time shifted toward audio book consumption.

I joined Goodreads in mid-2009. Here is my year in books summary since then:

Of the 33 books I read in 2025, 28 were audiobooks. Four of the books were re-reads (all of these were audiobooks). Six of my books were listen-alouds with the kids.

A complaint against the author

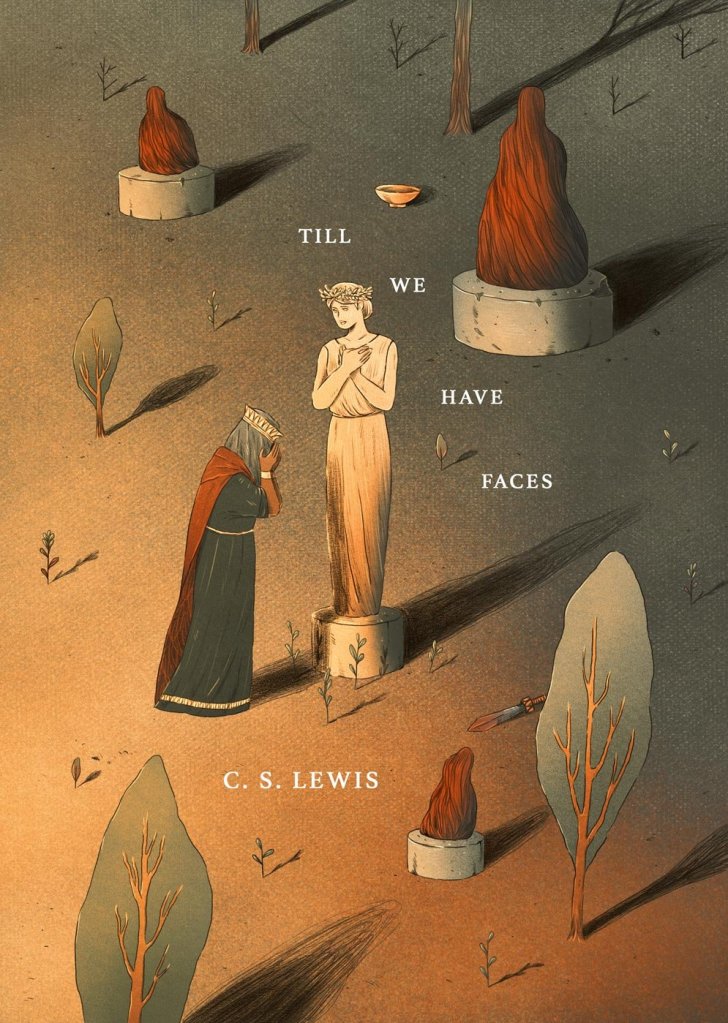

I recently finished reading C. S. Lewis’s book, Till We Have Faces. To the right is a cover illustration by Hannae Kim.

Till We Have Faces is widely acclaimed, and Lewis himself considered it to be “far and away my best book.” I was prepared to appreciate it greatly, but it fell a bit flat and felt a bit facile for me.

First, for a conversion story, it is surprisingly lacking in a sequence of obvious confession and repentance. Can we be sure that Orual has recognized all of her sins and failures?

Second, the most emotionally powerful portions of the second part—Orual’s being enabled to assist her sister in her travails—are watered down by having occurred only in dreams.

This is a specific example of a wider problem: the second part is rushed and didactic; it hardly has the character of story, has an unclear climax, and lacks the engaging nature of the first part.

While this story has great potential, much of this potential is dissipated by these weaknesses.

II

After some days’ reflection, I am compelled to confess my foolishness and retract my prior complaint.

The short nature of the second part is not necessarily a defect, nor is it lacking in story-like quality even though it is functioning as a different kind of narrative from the first part. This structure in fact mirrors the pattern of accusation, unmasking, and revelation that takes place at the end of a detective novel. We have been looking forward to being gathered with Poirot in the parlor for a very long time. There is a definitive climax and it is that accusation-revelation.

I am increasingly struck by the nature of the title and Orual’s corresponding statement, “How can they meet us face to face till we have faces?” By this Orual means that our innermost character, which we often keep hidden even from ourselves, is fully exposed. Orual’s complaint is her confesssion, because it is a compulsive vomiting of all of the ugliness and bitterness that she held inside. Her wearing a veil to cover her physical ugliness was a symbol of this greater masking; but ironically her obsession with her outer mask was part of how she hid from herself the existence of this greater mask.

Orual is physically unmasked and then unmasks her inner self, revealing “my real voice.” Her confession that “Yes,” she was answered is her repentance; she recognizes the thorough ugliness of it all. And this is the climax of the story.

But this is not a typical detective story; it is a Chestertonian one. The climactic revelation is followed by a second revelation. And this second revelation is not primarily that Orual’s dreams have a different meaning, but that her whole life is shot through with a different meaning.

The ways that Orual sacrificially helps her sister appear to occur entirely in dreams. But this does not necessarily mean that Orual is not actually suffering or giving of herself. In fact, since Orual’s life and strength are so suddenly and greatly weakened, it seems she is genuinely suffering through the course of these dreams. But in addition to this, Orual’s entire life has been consumed by a desire—selfish, but real—for the good of Psyche. In her confession and repentance, this desire is purified and, I suggest, Orual’s lifelong prayers are equally purified, and answered by the gods as such.

But it is also significant that the one real, non-dreamlike, active, and lifelong participation that Orual is revealed to have had in Psyche’s suffering was to serve as a harm, as an obstacle and temptation. The thought that Orual thus contributed to her sister’s maturation, purification, and sanctification does not seem immediately as beautiful or as emotionally powerful as the thought that Orual had helped her sister through other trials. But it is beautiful; a deeper, darker kind of beauty. What’s more, the reciprocal nature of this exchange, of this shared salvation, is more obvious than it is in the other exchanges—Psyche, in passing the test, herself becomes a means of Orual’s obtaining forgiveness and salvation.

If anyone intends the journey to Berea, let him bring this book for a traveling companion.

Anxious

Usually when I use the word “anxious” I have Edwin Friedman in mind. However, following are quotes and reflections from John Williamson Nevin’s The Anxious Bench.

My friend Jon observes that, while the anxious bench and even the altar call may have disappeared from many churches, reformed charismatic churches have an “anxious mic,” that is, the “prophecy mic.” In my experience, the absence of a confession and absolution from worship leaves a gap that needs filling. If there is a prophecy mic then it is frequently filled by the most anxious church members reassuring one another. By this means women often preach to the church.

I think it is interesting that the modern answer proposed for dead formalism is an equally dead emotionalism. Both are dead externalisms. Perfume will not awaken a dead body.

Study, and the retired cultivation of personal holiness, will seem to their zeal an irksome restraint; and making their lazy, heartless course of preparation as short as possible, they will go out with the reputation of educated ministers, blind leaders of the blind, to bring the ministry into contempt, and fall themselves into the condemnation of the devil. Whatever arrangements may exist in favor of a sound and solid system of religion, their operation will be to a great extent frustrated and defeated, by the predominant influence of a sentiment, practically adverse to the very object they are designed to reach. . . .

False views of religion abound. Conversion is everything, sanctification nothing. Religion is not regarded as the life of God in the soul, that must be cultivated in order that it may grow, but rather as a transient excitement to be renewed from time to time by suitable stimulants presented to the imagination. A taste for noise and rant supersedes all desire for solid knowledge. The susceptibility of the people for religious instruction is lost on the one side, along with the capacity of the ministry to impart religious instruction on the other. The details of christian duty are but little understood or regarded. Apart from its seasons of excitement, no particular church is expected to have much power. Family piety, and the religious training of the young, are apt to be neglected. (63-64)

It is certainly a little strange, that the class of persons precisely who claim to be the most strenuous, in insisting upon unconditional, immediate submission to God, scarcely tolerating that a sinner should be urged to pray or read the bible, lest his attention should be diverted from that one point, are as a general thing nevertheless quite ready to interpose this measure in his way to the foot of the cross, as though it included in fact the very thing itself. And yet a pilgrimage to the Anxious Bench, is in its own nature as much collateral to the duty of coming to Christ, as a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. In either case a false issue is presented to the anxious soul, by which for the time a true sight of its circumstances is hindered rather than promoted. (68)

A low, shallow, pelagianizing theory of religion, runs through it from beginning to end. The fact of sin is acknowledged, but not in its true extent. The idea of a new spiritual creation is admitted, but not in its proper radical and comprehensive form. The ground of the sinner’s salvation is made to lie at last in his own separate person. The deep import of the declaration, That which is born of the flesh is flesh, is not fully apprehended; and it is vainly imagined accordingly, that the flesh as such may be so stimulated and exalted notwithstanding, as to prove the mother of that spiritual nature, which we are solemnly assured can be born only of the Spirit Hence all stress is laid upon the energy of the individual will, (the self-will of the flesh,) for the accomplishment of the great change in which regeneration is supposed to consist. . . .

Religion does not get the sinner, but it is the sinner who “gets religion.” Justification is taken to be in fact by feeling, not by faith; and in this way falls back as fully into the sphere of self-righteousness, as though it were expected from works under any other form. In both the views which have been mentioned, as grounded either in a change of purpose or a change of feeling, religion is found to be in the end the product properly of the sinner himself. It is wholly subjective, and therefore visionary and false. The life of the soul must stand in something beyond itself. Religion involves the will; but not as self-will, affecting to be its own ground and centre. Religion involves feeling; but it is not comprehended in this as its principle. Religion is subjective also, fills and rules the individual in whom it appears; but it is not created in any sense by its subject or from its subject. The life of the branch is in the trunk. (114-116)

To acquire, in any case, true force, [the will] must fall back on a power more general than itself. And so it is found, that in the sphere of religion particularly, the pelagian theory is always vastly more impotent for practical purposes, than that to which it stands opposed. The action which it produces may be noisy, fitful, violent; but it can never carry with it the depth, the force, the fullness, that are found to characterize the life of the soul, when set in motion by the other view. (127)

This spiritual constitution is brought to bear upon [man] in the Church, by means of institutions and agencies which God has appointed, and clothed with power, expressly for this end. . . . Due regard is had to the idea of the Church as something more than a bare abstraction, the conception of an aggregate of parts mechanically brought together. It is apprehended rather as an organic life, springing perpetually from the same ground, and identical with itself at every point. In this view, the Church is truly the mother of all her children. They do not impart life to her, but she imparts life to them. Here again the general is felt to go before the particular, and to condition all its manifestations. The Church is in no sense the product of individual christianity, as though a number of persons should first receive the heavenly fire in separate streams, and then come into such spiritual connection comprising the whole; but individual christianity is the product, always and entirely, of the Church, as existing previously and only revealing its life in this way. Christ lives in the Church, and through the Church in its particular members. . . .

Where it prevails, a serious interest will be taken in the case of children, as proper subjects for the Christian salvation, from the earliest age. Infants born in the Church, are regarded and treated as members of it from the beginning, and this privilege is felt to be something more than an empty shadow. The idea of infant conversion is held in practical honor; and it is counted not only possible but altogether natural, that children growing up in the bosom of the Church, under the faithful application of the means of grace, should be quickened into spiritual life in a comparatively quiet way, and spring up numerously, “as willows by the water-courses,” to adorn the Christian profession, without being able at all to trace the process by which the glorious change has been effected. Where the Church has lost all faith in this method of conversion, either not looking for it at all, or looking for it only in rare and extraordinary instances, it is an evidence that she is under the force of a wrong religious theory, and practically subjected, at least in some measure, to the false system whose symbol is the Bench. If conversion is not expected nor sought in this way among infants and children, it is not likely often to occur. All is made to hang methodistically on sudden and violent experiences, belonging to the individual separately taken, and holding little or no connection with his relations to the Church previously. Then as a matter of course, baptism becomes a barren sign, and the children of the Church are left to grow up like the children of the world, under general most heartless, most disastrous neglect. The exemplifications of such a connection between wrong theory and wrong practice, in this case, are within the reach of the most common observation. (129-132)

How prophetic.

Persuasion

Some favorite quotes from Jane Austen’s Persuasion:

Anne’s object was, not to be in the way of anybody; and where the narrow paths across the fields made many separations necessary, to keep with her brother and sister. Her pleasure in the walk must arise from the exercise and the day, from the view of the last smiles of the year upon the tawny leaves, and withered hedges, and from repeating to herself some few of the thousand poetical descriptions extant of autumn, that season of peculiar and inexhaustible influence on the mind of taste and tenderness, that season which had drawn from every poet, worthy of being read, some attempt at description, or some lines of feeling. She occupied her mind as much as possible in such like musings and quotations . . .

As soon as she could, she went after Mary, and having found, and walked back with her to their former station, by the stile, felt some comfort in their whole party being immediately afterwards collected, and once more in motion together. Her spirits wanted the solitude and silence which only numbers could give.

Anne, judging from her own temperament, would have deemed such a domestic hurricane a bad restorative of the nerves, which Louisa’s illness must have so greatly shaken. But Mrs Musgrove, who got Anne near her on purpose to thank her most cordially, again and again, for all her attentions to them, concluded a short recapitulation of what she had suffered herself by observing, with a happy glance round the room, that after all she had gone through, nothing was so likely to do her good as a little quiet cheerfulness at home. . . .

Everybody has their taste in noises as well as in other matters; and sounds are quite innoxious, or most distressing, by their sort rather than their quantity. When Lady Russell not long afterwards, was entering Bath on a wet afternoon, and driving through the long course of streets from the Old Bridge to Camden Place, amidst the dash of other carriages, the heavy rumble of carts and drays, the bawling of newspapermen, muffin-men and milkmen, and the ceaseless clink of pattens, she made no complaint. No, these were noises which belonged to the winter pleasures; her spirits rose under their influence; and like Mrs Musgrove, she was feeling, though not saying, that after being long in the country, nothing could be so good for her as a little quiet cheerfulness.

She was deep in the happiness of such misery, or the misery of such happiness, instantly.

“It is a sort of pain, too, which is new to me. I have been used to the gratification of believing myself to earn every blessing that I enjoyed. I have valued myself on honourable toils and just rewards. Like other great men under reverses,” he added, with a smile. “I must endeavour to subdue my mind to my fortune. I must learn to brook being happier than I deserve.”

Beowulf

Tolkien’s translation is okay:

Then that warrior turned his horse, and thereupon spake these words: ‘Time it is for me to go. May the Almighty Father in his grace keep you safe upon your quests! To the sea will I go, against unfriendly hosts my watch to keep.’ (22)

Heaney is better:

. . . then the noble warrior

wheeled on his horse and spoke these words:

“It is time for me to go. May the Almighty

Father keep you and in His kindness

watch over your exploits. I’m away to the sea,

back on alert against enemy raiders.” (23)

But Wilson’s rendition is the best (it must be read aloud):

Then he wheeled and he went, wished them Godspeed,

“May the great Father favor you and find you in kindness,

Bestowing His blessings and backing your exploits.

For myself I must go and make my way back

To the coast where I can keep my watch up for raiders.” (17)

Metábasis eis állo génos (3-8)

I’ve just finished Hannah Coulter and am working my way through Jayber Crow. Delightful books!

One thing among many that strikes me is the occurrence of faintly familiar names like Proudfoot and Otha. It turns out that there is a bit of Cantuckee in the Shire! From Guy Davenport:

The closest I have ever gotten to the secret and inner Tolkien was in a casual conversation on a snowy day in Shelbyville, Kentucky. I forget how in the world we came to talk of Tolkien at all, but I began plying questions as soon as I knew that I was talking to a man who had been at Oxford as a classmate of Ronald Tolkien’s. He was a history teacher, Allen Barnett. He had never read The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. Indeed, he was astonished and pleased to know that his friend of so many years ago had made a name for himself as a writer.

“Imagine that! You know, he used to have the most extraordinary interest in the people here in Kentucky. He could never get enough of my tales of Kentucky folk. He used to make me repeat family names like Barefoot and Boffin and Baggins and good country names like that.”

And out the window I could see tobacco barns. The charming anachronism of the hobbits’ pipes suddenly made sense in a new way. The Shire and its settled manners and shy hobbits have many antecedents in folklore and in reality—I remember the fun recently of looking out of an English bus and seeing a roadsign pointing to Butterbur. Kentucky, it seems, contributed its share.

Practically all the names of Tolkien’s hobbits are listed in my Lexington phone book, and those that aren’t can be found over in Shelbyville. Like as not, they grow and cure pipe-weed for a living. Talk with them, and their turns of phrase are pure hobbit: “I hear tell,” “right agin,” “so Mr. Frodo is his first and second cousin, once removed either way,” “this very month as is.” These are English locutions, of course, but ones that are heard oftener now in Kentucky than in England.

I despaired of trying to tell Barnett what his talk of Kentucky folk became in Tolkien’s imagination. I urged him to read The Lord of the Rings but as our paths have never crossed again, I don’t know that he did. Nor if he knew that he created by an Oxford fire and in walks along the Cherwell and Isis the Bagginses, Boffins, Tooks, Brandybucks, Grubbs, Burrowses, Goodbodies, and Proudfoots (or Proudfeet, as a branch of the family will have it) who were, we are told, the special study of Gandalf the Grey, the only wizard who was interested in their bashful and countrified ways.

I’ve struggled for awhile to understand the key differences between incrementalism and abolitionism, since I admire some men in each camp and these differences seem to be obscured in the discussion. I’ve come to conclude two key points in favor of abolitionism:

- First, positively, abolitionists rightly point out that incremental legislation gives away the farm. I think you could distill the most compelling case for abolitionism as follows: “You know, brother, I could be an incrementalist too if we knew that incremental legislation was truly passing over some babies. It would be a sad thing but not an abominable thing. We know that we are incremental in this way when we pass over New York by starting in Oklahoma. And we know that we are incremental in this way by passing over a million other partialities in the law and focusing on this one. Maybe God has even called you to address those partialities instead of abortion. But it is so important to realize that incremental abortion legislation doesn’t actually pass over the Downs syndrome babies and the pre-heartbeat babies and the IVF babies. It explicitly offers them up to slaughter and essentially encodes in the law the position that they are non-persons. That is a disastrous compromise and I can’t support it in any way, even though I still give thanks to God for a life saved.”

- Second, it is not true that the abolitionists are pursuing a Procrustean outcome that trades one partiality for another. It is not the case that abolitionism wants to automatically send every father and mother to the chair. Rather, I’ve heard the abolitionist position summarized as “we just want to recognize life as life and practice common law.” Common law makes room for degrees—or in Biblical terms, distinctions between high-handed sins and sins of inadvertency or being led astray.

A hearty amen to this: An Open Letter to Justin Trudeau and the Federal Government.

One of the exceptions I take to the Westminster Confession of Faith is its statement that we should not consider God to be the “author of sin” in WCF 3.1 and 5.4. I agree that God is not “responsible for sin” nor “accountable for sin” nor an “approver of sin” (e.g., Heb. 4:15), but I think that the common sense of author has changed today, and I believe we should be able to fruitfully speak of God as the author of all things in the same way we speak of him as ordaining “whatsoever comes to pass.”

Wayne Grudem offers the language of God as author (chapter 16 section B.6) but in recent editions he added a clarification: “the analogy of an author (= writer, creator) of a play should not lead us to say that God is the ‘author’ (= actor, doer, an older sense of ‘author’) of sin, for he never does sinful actions, nor does he ever delight in them.” I agree with Grudem’s distinction.

John Frame comments on this in The Doctrine of God (see here) and I suspect he is the reason behind Grudem’s adding the qualification above. Frame, too, cautions that there are two senses in which we might use “author,” and I agree with the distinction he makes: “One might object to this model that it makes God the ‘author’ of evil. But that objection, I think, confuses two senses of ‘author.’ As we have seen, the phrase ‘author of evil’ connotes not only causality of evil, but also blame for it. To ‘author’ evil is to do it. But in saying that God is related to the world as an author to a story, we actually provide a way of seeing that God is not to be blamed for the sin of his creatures.”

Reason

In clearing up the underbrush of privilege and prejudice, liberalism or rationalism was convinced that it held in its hand the naked truth, undisguised, unstained by dogma or tradition. Reason discovering nature can test everything by experiment. There is no room for traditional habits: fashion takes the place of habit. But it is precisely fashion which enslaves Reason. The philosophizing mind has its prison of sensuality and drudgery exactly like a pupil of the Jesuits or a child in a backwoods village. Its fairy-tale and its prejudice are not dependent upon miracles or dogmas or incense or witchcraft, but the apparatus of Reason is subject to the same laws of sensuous disguise as any other part of the human soul. Superstition sends us to the medicine man, physical pain to the physician. We have a native sense that urges us on toward Reason and Philosophy: this sense is curiosity. Without a sense for novelty, no thinker can succeed or affect the life of the community. The self-indulgence of Reason is its predilection for the new. The newspaper is the true expression of this quality of philosophical perception, the sensuous form which enables man to recollect truth in its disguise as news. New facts and new ideas inflame our imagination. Without this flame the best idea, the wisest thought, remains useless. Any influence upon our senses is useless so long as our senses do not react. Indifference is a state of perfect equilibrium. When we feel neither cold nor warm, our internal thermometer is not registering anything. As long as we feel neither joy nor pride, our emotional system is quiescent. Philosophy has recognized the external dependence of all our senses. It is aware that they are all based on impressions, and react to influences from outside.

Now Reason is exactly the same kind of servant. It serves us well whenever its proper centre is stimulated. It is created and given to us for the purpose of distinguishing between new and old. It begins to move and to be stimulated by sensations which are new, unheard of. Reason is tickled by novelty. The nineteenth century changed the oldest truths into sensational news. We are willing to believe that the wind bloweth where it listeth, or that to him who hath shall be given, if we read it on the front page of our newspaper as the latest cable from Seattle. As the latest news in the newspaper, the oldest truth is welcome to Reason. The Age of Reason reveals truth by proceeding from news to news. It believes that the age of Revelation is gone; it believes in Enlightenment. But it itself is wholly based on Revelation. Reason cannot understand eternity or old age. It scorns tradition, ancien régime, customs, irrational weights or measures. It is clear, precise; but it also destroys everything which cannot be made either bad or happy news. Anything that is not willing to break out or happen or change is hidden to Reason. The nineteenth century forgot all eternal truth which was not ready to step down into the arena of Latest News, telegrams and publicity. A man had to become a sensation lest he be a failure.

. . .

These, then, are the “grandeurs et misères” of the victory of Reason. Reason, abstract and unreal, without roots in the soil, without rhythm in its movements, cannot govern its world without submitting to the directing power of sensation.

Today we are somewhat tired of this self-indulgence of Reason. The titillation of our sense of novelty is expensive and ruinous, because world, facts, truth and values lose their roots in the timeless when they are made to depend upon being rediscovered from time to time. Under the dictatorship of Reason, man begins to live like a solitary and one-celled animal. This unicellular life can get nowhere except by eating and swallowing. Multicellular life can depend upon older achievements without eating and digesting them. The modern society of the nineteenth century kills everything which cannot be swallowed in the form of news and sensations. It is unicellular. Now civilization does not form visible cells; its cells consist of generations, ages, periods. The repressive and outstanding feature of the age of Reason is its “single-aged,” one-generation character. Such an age may go on for two hundred years; but it will always remain a one-generation affair as long as its values depend on reproduction in the form of novelty. We meet reality through various senses. Any sense which states a difference is able to inform us. A consideration of our modern life will reveal how much of its information is based on a mere sense of curiosity. Curiosity arranges the things of the universe according to their quality of being new; and this produces an order of things of remarkable futility. The movie star comes to the foreground, wisdom is ridiculed, forests are sacrificed without a qualm because they grow so slowly, and skyscrapers are adored because they go up so fast. It is a very limited outlook on the universe which we gain through our instruments for news. There are other instruments, like hunger, reverence, patience, faith, which work in a different way and discover very different parts of the world.

The sense of novelty has been organized in the last hundred and fifty years as our main highroad of information. We say: it has been organized. The nineteenth century did not make discoveries or inventions in the same way as any other period of history. It invented the technique of invention; it formulated the methods of discovery. The secret of the French Revolution is the organization of discovery. We no longer stumble from one invention to the next; we have learned to plan our inventions and discoveries.

The sensation of novelty is sanctified by the campaigns carried on in our laboratories into the unknown. But like any sacrament, this one is stained by terrible superstitions. No one wishes to minimize the miracles performed in the laboratory; but we must overcome this appalling destruction of family, discipline, faith, by curiosity and by the growing paralysis of the rest of our senses. Because everybody has been trained in curiosity, most people have neglected their other senses; our deeper, wiser, better and more important links with reality have degenerated under our system of newspapers, radios, phonographs, movies, with their organization of novelty. They are the bane of modern life. The prohibition of news would restore the peace of many families. Truth will die if the masses see it based on nothing but novelty. Truth is not new, it is all around us. It was before we were. The original thinker knows that true originality consists in being as old as creation. (Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, Out of Revolution, 248-253)

Rosenstock-Huessy’s comments on the organization of scientific progress call to mind Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Each revolution in history—and doubly so the coming transition from empire to tribe—involves a gestalt shift. Usually this is a generational shift because old wineskins cannot handle new wine. And until it happens, we often cannot see clearly how it will take form, though we know that the old ways will cease to work, things will fall apart, and the new ways will not be exactly like anything that has come before. But what is exciting about this is that, if you are willing to heed the prophets, you can still give your children a head start by freeing them from service to the fashionable–idols and helping them to love what is true and good and beautiful.

Metábasis eis állo génos (2-34)

Mark Horne writes about God’s perfect justice and how God acts generationally (part 1, part 2, part 3), concluding as follows (but you should read all three):

We need to distinguish between descendants being affected by the sins of their ancestors and their being guilty of those sins. . . . So yes, sometimes God’s public justice destroys people who didn’t personally commit the injustice. The young and marginal in Sodom and Gomorrah got burned up with the rest. Achan’s family (along with the warriors who first attacked Ai) got destroyed for his sin that some may not have had a part in. Those deaths are punishments of the sinner (Achan and whoever was an accessory) but their personal deaths are justified in Genesis 3, not in what Achan did. Their deaths are, on a personal level, no different than the deaths of Job’s children who were killed because he was righteous.

Three key points to keep in mind are that (1) death comes to all of us in Adam; (2) it is not necessarily judicial (for which see the moving 1 Kings 14:13); and (3) the Bible often hides for us either a distinction that God is making, or at least his reasons for making it. One example of this is the sons of Saul in 2 Samuel 21; it is clear that not all of Saul’s sons are put to death, but we are not let in on the (obviously) righteous distinction that was made. Another example is the family of Korah in Numbers 16; it seems from this passage that God put the entire family to death, but Numbers 26:11 tells us that at least some of Korah’s children were preserved, and it is likely their offspring are the Korahites faithfully serving in God’s house in 1 Chronicles 26 and several of the Psalms.

This is a good time to remember that Jephthah did not offer up his daughter. However, God was righteous in commanding Abraham to offer up Isaac.

I revisited Deuteronomy 20 wanting to decide whether “civilian” was a proper distinction for jus in bello. I’m not sure that it is. At the city level, all of the men of a contumacious city are subject to the sword. I’m not sure to what degree this extends beyond the level of a city; I’m not convinced that Judges 19-21 is a righteous example. It’s also worth reflecting on the typology of trees and thorns; what are fruit trees? Are they women?

I’m so thankful for the elders of the CREC!

The Lord’s table must reflect the diversity of his body (Galatians 2, James 2, 1 Corinthians 11). Now, James teaches the church not to engage in partial social engineering—as if we would fly in someone from Saskatchewan, or work especially hard to bring in a Florida man, or begin conducting our services with Hungarian translation. And since the old covenant was completely torn down in AD 70, the church does not even go “to the Jew first” but to all men. But James does command us to welcome all those whom God sends our way. Therefore it is of utmost urgency that the church baptize her little ones and welcome them to the table. In the new covenant, where holiness and cleanness are now contagious rather than death (Matthew 9, 1 Corinthians 7), our little ones are now more welcome in Jesus than ever before (Mark 10; you can be sure that Jesus’s blessings are not mere platitudes); “your children shall come back” (Jeremiah 31), “they all shall know Me, from the least of them to the greatest . . . for I will forgive their iniquity” (Jeremiah 31, Hebrews 8). If we do not welcome our little ones to their Lord’s table, then we fail to “discern the body [of Christ]” and become “guilty” of his body and blood (“for this reason many are weak and sick”); we are “out of step with the truth of the gospel;” and we “stand condemned” as Peter and the disciples—ultimately teaching the world a lie about the place of little ones in a polis.

This is why they look at me with suspicion, seeing me as a sort of sheep in wolf’s clothing. (Conversations with René Girard, 181)

As the scapegoat mechanism has been revealed, we do not return directly to it, that is, we do not directly accuse the victim of having done something. We don’t blame them directly. But the scapegoat mechanism continues to work, though in a different way: the politically correct movement accuses their opponents of creating scapegoats. They accuse them of victimizing others. It’s like Christianity turned upside down: they take whatever is left of Christian influence, whatever is left of Christian language, but to opposite ends, in order to perpetuate the scapegoat mechanism. (Conversations with René Girard, 182)

Christianity never had this goal. It never sought to organize society. (Conversations with René Girard, 182)

Today people in academia are not even trying to be honest. (Conversations with René Girard, 183)

It seems like the ancient, primitive fatalities, temporarily discarded by the light of the prophets and the Gospel, are coming back. In the Bible, the protection of children appears alongside the protection of the handicapped, lepers, cripples. These are the preferential victims of ancient societies, and we understand we must protect them. We still protect crippled people, handicapped people, but in the center of it all we find a sort of cancer growing, which is the return to infanticide. This is a decisive argument, which few people will take into consideration: those who defend abortion are trying to make our society go back to pre-Christian barbarism. (Conversations with René Girard, 184)

This was a fascinating Twitter thread. I recently bought a Berkey filter thinking that the main benefits would be chlorine and fluoride filtering. But it seems like there are more benefits—and also that you might want to consider a filter even if you drink well water.

Metábasis eis állo génos (2-33)

Now is the time for states, counties, and municipalities to be enacting a great many sanctuary laws. You may have heard of this in relation to the second amendment, but we need to expand the idea to cover abortion, mask mandates, lockdowns, and vaccine mandates.

I’m in favor of the following tests for political office: (1) familiarity with the Bible, (2) familiarity with René Girard, and (3) familiarity with Edwin Friedman. I think this would solve a lot of problems.

There is one place where social distancing is against the law: the Lord’s weekly supper (Gal. 2). There is neither masked nor unmasked, vaccinated nor unvaccinated, but Christ is all and in all. Greet one another with a holy kiss. And go do likewise at your own tables and workplaces.

We saw a velvet ant on a walk yesterday; I had never seen or heard of them before. They are actually wasps, and are sometimes called “cow killers,” not because their sting is dangerous but because it is painful:

James Jordan writes about long-haul postmillenialism:

As an orthodox, Bible-believing Christian who has been a postmillennialist for nearly twenty years, I think about this when I look at the postmillennial resurgence in America today. Is it going to be a true, Biblical postmillennialism? Will it have room for Ecclesiastes? Will it have room for cross-bearing? Will it see that for us God really is incomprehensible, though not inapprehensible? Will it be clay in the Master’s hand?

I do think that some day we will be wrestling with the chains of Pleiades and the cords of Orion.

I am not necessarily hostile to all the things which I do not mention in my writing. (Conversations with René Girard, 60)

Nothing would be easier [than to put humanity back on the right path] if we wanted to do it: but we don’t want to. To understand human beings, their constant paradox, their innocence, their guilt, is to understand that we are all responsible for this state of things because, unlike Christ, we’re not ready to die. (Conversations with René Girard, 73)

Revelation is dangerous. It’s the spiritual equivalent of nuclear power.

What’s most pathetic is the insipidly modernized brand of Christianity that bows down before everything that’s most ephemeral in contemporary thought. Christians don’t see that they have at their disposal an instrument that is incomparably superior to the whole mishmash of psychoanalysis and sociology that they conscientiously feed themselves. It’s the old story of Esau sacrificing his inheritance for a plate of lentils.

All the modes of thought that once served to demolish Christianity are being discredited in turn by more “radical” versions of the same critique. There’s no need to refute modern thought because, as each new trend one-ups its predecessors, it’s liquidating itself at high speed. . . . For a long time, Christians were protected from this insane downward spiral and, when they finally dive in, you can recognize them by their naïve modernist faith. They’re always one lap behind. They always choose the ships that the rats are in the midst of abandoning.

They’re hoping to tap into the hordes of people who have deserted their churches. They don’t understand that the last thing that can attract the masses is a Christian version of the demagogic laxity in which they’re already immersed. (Conversations with René Girard, 77)

Once the Soviet state is created, the Marxists see first of all that the wealth is drying up and then that economic equality doesn’t stop the various kinds of discrimination, which are much more deeply ingrained. Then, because they’re utopians, they say: “There are traitors who are keeping the system from functioning properly”; and they look for scapegoats. In other words, the principle of discrimination is stronger than economics. It’s not enough to put people on the same social level because they’ll always find new ways of excluding one another. In the final analysis, the economic, biological, or racial criterion that is responsible for discrimination will never be found, because it’s actually spiritual. Denying the spiritual dimension of Evil is as wrong as denying the spiritual dimension of Good. (Conversations with René Girard, 82)

I think the reason we talk so much about sex is that we don’t dare talk about envy. The real repression is the repression of envy. (Conversations with René Girard, 100)

What people call the partisan spirit is nothing but choosing the same scapegoat as everybody else. (Conversations with René Girard, 133)

We have experienced various forms of totalitarianism that openly denied Christian principles. There has been the totalitarianism of the Left, which tried to outflank Christianity; and there has been totalitarianism of the Right, like Nazism, which found Christianity too soft on victims. This kind of totalitarianism is not only alive but it also has a great future. There will probably be some thinkers in the future who will reformulate this principle in a politically correct fashion, in more virulent forms, which will be more anti-Christian, albeit in an ultra-Christian caricature. When I say more Christian and more anti-Christian, I imply the future of the Amit-Christ. The Anti-Christ is nothing but that: it is the ideology that attempts to out christianize Christianity, that imitates Christianity in a spirit of rivalry. (Conversations with René Girard, 141)

Mission

My favorite quotes from Peter Leithart’s Theopolitan Mission:

The principle of ministry in the church is simple: “Let all things be done for edification” (1 Cor 14:26). This is the rule: Do everything you do to complete Christ’s body. (39)

Macedonians make a koinonia contribution to poor saints in Jerusalem (Rom 15:26). As Paul sees it, they don’t throw money at a problem from a distance. Rather, their generous gifts overcome distance, joining Macedonian Gentiles and Jerusalem Jews in one fellowship of the Spirit. Material gifts have a quasi-sacramental power to join the members of the church into one body. (50)

A church isn’t carrying out the mission of Jesus if it doesn’t gather on the Lord’s Day at a common table. (54)

Conflict is no accident, nor is it avoidable. Suffering is the only path into the kingdom, an inevitable part of mission. (71)

Like the ark, the church receives and preserves the treasures of the world (Rev 21:24) so they can be purged, transfigured, and brought out again to adorn creation. As worlds collapse, the world’s riches are kept safe in the ark of the church. All things are gathered into the church so that all things can disembark into a new creation. Noah performs this magic only once, but Jesus does it continuously. Treasures flow continuously into the ark of Christendom. The church has received the treasures of Greek and Roman art, philosophy, and politics, to purify them and bring them to fulfillment. It will plunder the gold of China, Japan, and India, of the Masai and Zulu, of Arabia and Iraq and Afghanistan. Treasures from the city of man enter the city of God so they can return to the city of man, renewed. The city of man enters the ark of God so it can become more perfectly what it’s supposed to be, more perfectly an image of heavenly Jerusalem.

The church pilots the world. What happens in the holy church guides what happens outside. If the church is unfaithful, leaves her first love, and turns to false teachers, Jesus will move the lampstand and abandon the house (Rev 2-3). If the church keeps her lamps burning, continuously supplied by the oil of the Spirit, the world will be full of light. (79)

I wonder sometimes if any of my international colleagues are secret brothers and sisters.

Transformed by the Eucharist, our making is freed from pure utility and functionality. Utility is good. A woodworker makes tables for meals, weavers make cloth for clothing, metalworkers make wires for electricity and rebar to strengthen walls. All these forms of making have practical ends. But when we make in order to offer our fruit to God in praise, we transcend mere usefulness. The cobbler doesn’t just cover bare feet; he cobbles for the glory of God. At the same time, the sanctuary frees us from the sterile circularity of making for its own sake, the effete snobbery of “art for art’s sake.” Making Eucharistically, a craftsman makes for God. “Art for art’s sake” is a sign of decadence. It’s a symptom of the decay of liturgy. (88-89)

A flood is coming. It’s already sweeping away the world as we know it. The world we know will be submerged as the Lord turns the world upside down and gives it a sharp shake (Hag 2:6-7).

It’s not the end of everything. Creation will survive, and civilization will be reborn. Jesus will steer the ark of his church through the storm. As the clouds gather, as the thunder begins to roll, as the deluge crashes down, we’re called to continue the often-imperceptible work of building the ark of Jesus. With our lives scripted by the Scriptures that reveal the Christ, we cling to the apostolic gospel, gather to break bread, share our material and Spiritual gifts, offer a continuous sacrifice of prayer and song. We preach the good news in false churches and public squares, endure the rage of the mob, suffer with Jesus so we may share His glory. We confront idols and demons and call all men from darkness to light, from Satan to the living God (Acts 26:18). In the Last Adam, we’re made right-makers, grateful makers whose making is an act of worship. Some will slip, lizard-like, into palaces (Prov 30:28) and gain a hearing before Prime Ministers and Presidents.

As we do these things, we preserve the treasures of the past and, by the alchemy of the Spirit, transfigure ancient treasures into new. When the storm is over and the flood waters recede, we’ll have and be the seeds of a new creation. We’ll flow like living water to fertilize the wasteland.

If you’re a Christian, that’s what you’re doing. Your life may not look like a big deal. You’re kind to your neighbors, serve your brothers and sisters in church, gather each week to receive God’s Word and God’s Bread. You train and teach your children as disciples; you love your husband or wife. You’re an honest and productive employee, an attentive employer, an entrepreneur or bureaucrat in a well-established institution. You do and make, but no one notices. . . .

You feel invisible, but that’s an optical illusion. You’re participating in the biggest project imaginable. You’re joining with millions of others to build the self-building ark of Jesus. Through your witness and labor, a new world is taking form. You’re fighting the battle of the ages. You’re constructing the city of God among the cities of men in order to transform the cities of men to become more like the city of God. Nothing is small in the kingdom of Jesus.

There’s nothing to fear. We live in joy and expectant hope. Jesus is in the boat, and He calms the seas. The Carpenter of Nazareth will pilot his ark until it rests on a new Ararat, a new Eden, the garden-city where the river of life flows. (100-101)