Archive for the ‘Biblical Theology’ Category

Chiasm and creation in John

Hajime Murai has proposed a deep chiasm running the entire length of the book of John. I’ve been following along off and on in our church’s readings in John, and some of the parallels are striking; for example, John 4 paired with John 19, or Nicodemus questioning and later burying Jesus.

Murai includes the so-called pericope adulterae, John 7:53-8:11, in his outline. This is a disputed passage that almost certainly was not part of John’s original manuscript. However, I think that the chiastic parallels are actually stronger if this passage is omitted. Murai suggests that 7:53-8:11 parallels 10:1-21, and links the Pharisees’ lack of understanding. I suggest the following arrangement, starting with Murai’s pairing of living water with the raising of Lazarus:

7:37-39 Living water

7:40-44 Division and seeking to arrest

7:45-52 The shepherds of Israel

8:12-30 Light of the world

8:31-59 I AM

9:1-41 A man born blind healed; the blindness of the Pharisees

10:1-18 The great shepherd

10:19-39 Division and seeking to arrest

10:40-11:54 Crossing the Jordan and the healing of Lazarus

This serves as a small and secondary confirmation the disputed passage is not original to John.

The fact that the center of John involves a discussion of light and seeing and what is “above” is also striking, especially following a discussion of water. This suggests to me that Murai’s overall chiasm could be bracketed into seven sections that track the days of creation (central day four being the heavenly lights, following day three’s separation of land and waters).

History

Romans 11:17-24 reads:

But if some of the branches were broken off, and you, although a wild olive shoot, were grafted in among the others and now share in the nourishing root of the olive tree, do not be arrogant toward the branches. If you are, remember it is not you who support the root, but the root that supports you. Then you will say, “Branches were broken off so that I might be grafted in.” That is true. They were broken off because of their unbelief, but you stand fast through faith. So do not become proud, but fear. For if God did not spare the natural branches, neither will he spare you. Note then the kindness and the severity of God: severity toward those who have fallen, but God’s kindness to you, provided you continue in his kindness. Otherwise you too will be cut off. And even they, if they do not continue in their unbelief, will be grafted in, for God has the power to graft them in again. For if you were cut from what is by nature a wild olive tree, and grafted, contrary to nature, into a cultivated olive tree, how much more will these, the natural branches, be grafted back into their own olive tree. (ESV)

This has a significant implication for the history recorded into the Old Testament. It is possible both to be adopted into that history, and also to be disowned from that history. Thus, whatever its cultural make-up, Jesus’s church can claim the Old Testament as its own history: we were rescued from Egypt, we hung our harps on the willows, and we were preserved by Yahweh in exile.

It is also, of course, a sobering warning. It is possible for people and churches and cultures to live for centuries, even millennia, preoccupied with a history that is glorious but which has ceased to be your own.

Dragons and Leprosy

We watched the 1959 movie Ben Hur recently as a family and enjoyed it.

We watched the 1959 movie Ben Hur recently as a family and enjoyed it.

Contra the movie, I am not convinced that modern-day Hansen’s disease is linked with Biblical leprosy. They are very commonly confused, so I was not at all surprised. However, it did surprise and at first disappoint me to see leprosy healed just as soon as Jesus died; that seemed like a cheesy storytelling shortcut.

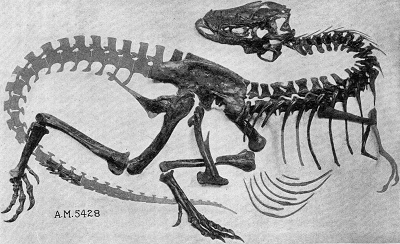

But upon reflection, it is true that Jesus brings us many great gifts apart from our deserving or even asking for them. A similar unasked-for miracle is recorded on that very day (Matt 27:52-54). And it is particularly striking that the kinds of leprosy described in Leviticus are nowhere quite exactly to be found today: just as today we no longer see the great dragons whose bones can still be found (e.g., Job 41, Isa. 27, 51), there is today no more leprosy of that kind. The last great leprous house was dismantled in AD 70 (Lev. 14:45, Matt. 24:2), so that we can say the death of Jesus truly did inaugurate the end of leprosy!

The great storyteller has seen fit to tie these transitions to the new covenant in Jesus. The great dragons are defeated, and there is now one washing that grants permanent access to the very throne of God, so that you could even say that it is now life rather than death that is contagious. This the movie portrayed well.

Baptized

2 Samuel 19 tells of the return of David to Jerusalem after the defeat of Absalom. Interestingly, it is said that Judah brings David back over the Jordan river, and a number of individuals who cross over to meet David are explicitly named. To properly show their repentance and receive David back, Judah first had to repudiate their rebellion and identify with David in his exile. These river crossings are very obviously a kind of baptism, a union with David in his exile and therefore his restoration.

2 Samuel 19 tells of the return of David to Jerusalem after the defeat of Absalom. Interestingly, it is said that Judah brings David back over the Jordan river, and a number of individuals who cross over to meet David are explicitly named. To properly show their repentance and receive David back, Judah first had to repudiate their rebellion and identify with David in his exile. These river crossings are very obviously a kind of baptism, a union with David in his exile and therefore his restoration.

A wise Benjaminite (Phil. 3:5) might have preached in Gilgal that day:

Men of Judah, do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into David were baptized into his exile? We were separated therefore with him by baptism into exile, in order that, just as David was revived from the pit by the glory of Yahweh, we too might walk in newness of life.

For if we have been united with him in an exile like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a restoration like his. We know that our old self was exiled with him in order that the rebellious nation might be brought to nothing, so that we would no longer belong to rebellion. For one who has been exiled has been set free from rebellion. Now if we have been exiled with David, we believe that we will also live with him. We know that David, being revived from the pit, will never be exiled again; exile no longer has dominion over him. For the separation he endured he endured to rebellion, once for all, but the life he lives he lives to God. So you also must consider yourselves dead to rebellion and alive to Yahweh in David.

Let not rebellion therefore reign in this nation, to make you obey its passions. Do not present your members to rebellion as instruments for unrighteousness, but present yourselves to God as those who have been brought from exile to life, and your members to God as instruments for righteousness. For rebellion will have no dominion over you, since you are not under law but under grace.

As it happened, the more foolish Benjaminites Sheba and Shimei did not heed this warning.

Therefore let us go to him outside the camp and bear the reproach he endured. (Heb. 13:13)

Thanksgiving

The Lord’s supper has historically been called the Eucharist, which means thanksgiving. This name is appropriate not just because the celebration of the supper properly involves prayers of thanksgiving (Luke 22:19, Matt. 26:27), but also because the supper is linked with the Passover feast, which in turn closely follows the form of the peace offering for thanksgiving (Lev. 7).

When the Old Testament refers to thanksgiving, this thanksgiving sacrifice is often in view. Thus, when God’s people enter his gates with thanksgiving (e.g., Ps. 95:2, 100:4), it is not just words of thanksgiving they carry, but a thanksgiving feast that they have come to celebrate. King David appointed a Levitical choir-orchestra (1 Chron. 15), whose performance before God was connected to the offerings and sacrifices (e.g., 2 Chron. 29). Giving praise to God in song is always linked with celebrating thanksgiving to him at his table.

We see this further in the book of Hebrews, where the language of “sacrifice of praise to God” (Heb. 13:15) exactly parallels the language of the Septuagint, which refers to a “sacrifice of praise” (Lev. 7:12 LXX) rather than a “thanksgiving sacrifice.” Similarly, Hebrews’ use of “continually” (also Heb. 13:15) repeats the expression used by the Septuagint to refer to the daily tribute offering (Lev. 6:20 LXX), which we have also linked to the Lord’s supper.

Thus, weekly Eucharist: because to enter God’s courts with praise is precisely to enter his gates with a thanksgiving feast; and because the fruit of our praise-giving lips is to celebrate a sacrifice of praise, that is, a thanksgiving feast.

Thanks to Peter Leithart for these reflections.

Enough

In the introduction to his book, God’s Companions: Reimagining Christian Ethics, Sam Wells writes:

. . . I take [there] to be a consistent majority strand in Christian ethics—the assumption that there is not enough, and thus that ethics is the very difficult enterprise of making bricks from straw. Scarcity assumes there is not enough information—we know too little about the human body, about the climate, about what makes wars happen, about how to bring people out of poverty, about what guides the economy. There is not enough wisdom—there are not enough forums for the exchange of understanding, for learning from the past, for bringing people from different disciplines together, and there is not enough intelligence to solve abiding problems. There are not enough resources—world population is growing, and there is insufficient access to education, clean water, food, health care, and the means of political influence. There is not enough revelation—the Bible is a lugubrious and often ambiguous document, locked into its time, unable to address the problems of today with the clarity required. Fundamentally, I suggest, this whole assumption of scarcity rests on there being not enough God. Somehow God, in creation, Israel, Jesus and the Church, and in the promise of the eschaton, has still not done enough, given enough, been enough, such that the imagined ends of Christian ethics are and will always be tantalizingly out of reach.

In contrast to this assumption of scarcity I suggest that God gives enough—everything that his people need. He gives them everything they need in the past: this is heritage; and everything they could possibly imagine in the future: this is destiny. He gives them the Holy Spirit, making past and future present in the life of the Church. He gives them a host of practices—ways in which to form Christians, embody them in Christ, receive all that God, one another, and the world have to give them, be reconciled and restored when things go wrong, and share food as their defining political, economic, and social act. The things he gives are not in short supply: love, joy, peace. The way these gifts are embodied is through the practices of the Church: witness, catechesis, baptism, prayer, friendship, hospitality, admonition, penance, confession, praise, reading scripture, preaching, sharing peace, sharing food, washing feet. These are boundless gifts of God. My complaint with conventional Christian ethics is that it overlooks, ignores, or neglects those things God gives in plenty, and concentrates on those things that are in short supply. In the absence of those things that are plentiful, it experiences life in terms of scarcity. My argument draws attention to those things that God gives his people and resists the temptation to scratch around for more.

On the other hand I argue that God gives his people not just enough, but too much. What I am doing is trying to account for there being more than one kind of problem in ethics. The first kind of problem is simply not wanting, or wilfully disregarding, the gifts of God, and setting about making one’s own. But there is another kind of problem, which is primarily about imagination. The “problem” is that there is too much of God. Whereas the first kind sees the difficulty being that God gives the wrong gifts, or not enough gifts, for the second kind the difficulty is that the human imagination is simply not large enough to take in all that God is and has to give. We are overwhelmed. God’s inexhaustible creation, limitless grace, relentless mercy, enduring purpose, fathomless love: it is just too much to contemplate, assimilate, understand. This is the language of abundance. And if humans turn away it is sometimes out of a misguided but understandable sense of self-protection, a preservation of identity in the face of a tidal wave of glory. Christian ethics should seek to ride the crest of that wave. It should be a discipline not of earnest striving, but of joy; a study not of the edges of God’s ways but of exploring the heart of grace. . . .

Thanks to Peter Leithart for the quote.

Fruit of the vine

In this post I move from consideration of weekly communion to the use of wine in the Lord’s supper. While both wine and grape juice may be permissible in communion, I believe that wine is preferable for a number of reasons. Herein I take it for granted that in the Bible wine is wine, strong drink is beer, both of these are gifts from God to be received with gratitude (which, like all gifts, can be abused), and that the use of grape juice in communion is a very modern and largely American development whose widespread practice is made possible only by the introduction of pasteurization by Welch almost 150 years ago. While it’s not my intention to establish these assumptions here, you can refer to Jeff Meyers’ essays on wine and beer (part 1, part 2) for some helpful considerations.

First we will consider some biblical-theological and typological reasons why the use of wine is most fitting in the supper. Then we will consider some practical considerations and precautions related to changing the church’s practice.

Do this. The New Testament uses the words “blood” and “fruit of the vine” rather than “wine” to refer to what we drink in the “cup” of the Lord’s supper. From this statement alone it is certain that Jesus is drinking wine. Genesis 49:11 and Deut. 32:14 strengthen this conclusion by establishing a Biblical imagery that specifically identifies wine as the blood of grapes. We will find further support as we look at the covenant meals that underlie the Lord’s supper, but for now we can say that using bread and wine are ways that we can more fully obey Jesus’s command to “do this.”

Passover. The Lord’s supper is strongly connected to Passover. It is interesting that only lamb and bread are directly prescribed for this feast. However, the Passover is a kind of peace offering; we see this in a couple of ways: first, that the ritual of the Passover matches that for the thanksgiving form of the peace offering. The peace offerings were the only offerings that worshippers could eat together with God. Like the Passover, the thanksgiving peace offering was an offering of an animal together with unleavened bread, and could not be eaten the following day. Second, Passover is described as a sacrifice (Deut. 16, Ex. 12, 34); of all the offerings, the peace offering is the only specific offering described as a sacrifice. Realizing this, we can now establish the connection between Passover and wine; as the people of Israel came to the promised land, God added a drink offering of wine to the ritual of the peace offering (Num. 15). We see additionally that other drink offerings were prescribed for Passover, although they seem to be connected to the ascension offering rather than the peace offering (Num. 28). Thus, wine is prescribed for Passover and therefore is also most appropriate for the Lord’s supper as its antitype.

Tribute offering. While the Lord’s supper is most closely connected to Passover, it is also connected to the tribute, or “grain” offering. We see this in that Jesus describes the supper as a remembrance (or memorial). Of all of the offerings, the tribute offering is the only specific offering described as a memorial. The tribute offering itself consisted of bread (Leviticus 2), oil, and frankincense (symbolizing the prayers of the saints), together with wine (Ex. 29). This offering was made twice daily by the priests. Since wine is prescribed for the daily tribute offering, it is also most fitting for the Lord’s supper as its antitype.

Tithes and offerings. Wine is also connected with the bringing of tithes and offerings. We see that when Abraham brought his tithe to Melchizedek, they shared a meal of bread and wine provided by the priest-king (Gen. 14). When Israel brought their tithe periodically to Jerusalem, God commanded them to feast on “whatever you desire—oxen or sheep or wine or strong drink, whatever your appetite craves” (Deut. 14). The giving of our tithes is partly to ensure that there is “food in my house” (Mal. 3); God wants to show forth his prodigal generosity to his people, and his serving an overflowing cup of wine to us at his table (Ps. 23) is part of this. Furthermore, the firstfruits offerings were distributed to the priests and Levites, and in particular “the best of the wine and of the grain” belonged to them (Num. 18, also Deut. 18). As a kingdom of priests, it is right for us to enjoy good bread and wine from God’s hand at his table.

Worship. We see further examples of this in Nehemiah 8, where the people are commanded to drink wine rather than mourn on God’s holy days, and in Ecclesiastes 9, where joyful consumption of bread and wine is commended to us. Certainly Ecclesiastes applies to all spheres of life, but it applies in a heightened way to worship and the eating of covenant meals at God’s house; with Asaph in Ps. 73 we recognize that the only way to unravel the mysteries set forth in Ecclesiastes is by faith, and especially as we worship God and eat together with him at his house.

Tryst. We have many images for what happens in corporate worship; one such is that it is a tryst between Jesus and his bride. Jesus is present with us in a special way above and beyond his presence day to day. We see an example of this with Ahasuerus and Esther (Esther 5, 7), and we see Jesus ensuring that a wedding has not only enough wine, but also the best wine (John 2). It is not lady Folly but lady Wisdom who sets her table with wine (Prov. 9). It is true that wine is a symbol of lovers offering themselves, and is contrast with love and blessings that exceed wine (Song of Solomon; Psalm 4; Isaiah 55). But this is precisely why it is a most fitting symbol for the Supper.

Blessing. We can go on to count more blessings that wine conveys. We see wine bringing kingly rest at the end of labors (Gen. 5 and the play on “nacham” and “Noach,” taken together with Gen. 9). Wine is said to cheer both God and man (Judges 9, Eccl. 2), to gladden man’s heart (Ps. 104) and life (Eccl. 10). Wine is used for health and healing (Luke 10, 1 Tim 5). All these points make wine a fitting picture of God’s goodness to us which serves to enrich its meaning in the supper. By settling for less than wine we cheapen the picture of God’s prodigality that Jesus intends for us to experience in the “cup of blessing.”

Priests and kings. While priests enjoyed the wine that was brought to God’s house, they were not allowed to enjoy it in God’s house at his own table (Lev. 10, Ezek. 44), nor did they even sit in God’s house (Heb. 10). Jesus, the king of kings, did enjoy a perpetual service of wine and beer in his own house, like earthly kings throughout history; consider Melchizedek the priest-king, Joseph the greater cupbearer to Pharaoh, wine a symbol for kingly Judah (Gen. 49), Nehemiah the cupbearer to Artaxerxes, Ahasuerus repeatedly drinking and serving wine, the cup in God’s hand throughout the Psalms and prophets, and the cups that Jesus pours out in Revelation. In the new covenant, we not only have the privilege of all being priests in God’s house, but have the greater privilege of being seated with Jesus as fellow sons and kings (Luke 22:30; Eph. 2). Thus, one of the great changes from the old covenant to the new is that Jesus seats and serves us at his table in his house, like so many Mephibosheths. We see the Corinthians taking this great new privilege to excess in their excitement, but to refuse the privilege of drinking wine with God in his house is in some sense to deny the newness and betterness of the new covenant, to be content with more distant fellowship with Jesus when he is willing to give us more.

Nazirite. This progression from covenant to covenant is related to the restrictions placed on the Nazirite, which included prohibition not only of wine but of all products of the grape (Num. 6; Judges 13; Luke 1, 7). What we can say about this is that it seems that the Nazirite underwent a temporary deprivation of the blessings of the promised land, reverting to a sort of wilderness estate in order to conduct a holy war campaign. This helps us to understand why Jesus refused wine on the cross (Matt. 26:29, 27:34; Mark 14:25, 15:23; Luke 22:18), as he was both acting as our high priest according to the law, and also acting as a Nazirite holy warrior. This culminated with the drinking of wine when he had finished his work (John 19:30), so that we can say that Jesus, having finished his work and sat down, is himself no longer under a prohibition of wine. Indeed, he shares it with us week to week as he serves us his supper at his table.

We admit that the appearance of Naziritehood twice in Acts (18, 21) is a strange occurrence. A plausible explanation is that it is a unique historical situation prior to the total destruction of the entire old-covenant system in AD 70; much like the “to the Jew first” practice of church planting, which we also no longer practice today. In any case, we hold that the law of the Nazirite has no relevance today and no bearing on the lawfulness of using wine in the supper.

Covenant sanctions. God provides wine to his people as part of his blessing for their faithfulness (Deut. 7, 11; Prov. 3) and as a benefit of their redemption and regeneration (Jer. 31). At the same time, God also promises to remove his blessing of wine as a consequence of discipline and judgment (Deut. 28; also many of the prophets). To serve wine to God’s church is therefore to show forth God’s blessing and favor; to withhold it is to show forth his displeasure and judgment.

Inspection. Wine is a symbolic double-edged sword in scripture. It is not just the case that believers are warned against excess and drunkenness (Prov. 20, 21, 23, 31; Eph. 5; 1 Tim. 3; Tit. 2). More than that, wine is actually a symbol of God’s judgment upon the wicked, so that we can speak of a sort of “wrathwine” (Ps. 75, throughout the prophets and Revelation). It is even as a symbol of the suffering of God’s people (Ps. 60) and of Jesus’s propitiatory suffering for us (Ps. 69). Drunkenness is therefore not only a sin but also a judgment for sin. Thus, just as baptism is a double-edged sword of judgment and salvation (you are either drowned like the Egyptians or saved like Israel), so wine has a discriminating effect (you are either made merry or made to reel and stagger). This is not inconsistent with the imagery of the Lord’s supper, in that Paul makes it out to be a discriminator between those who eat with Jesus and demons (1 Cor. 10), and between those who eat in unity and disunity (1 Cor. 10-11; Gal. 2). This makes the bread and wine of the supper a sort of “jealousy inspection” (as in Num. 5, which included a tribute-grain offering so that it had both bread and wine) whereby God inspects the faithfulness and unity of his bride. Thus, the use of wine is most fitting as we allow God to do his potent work of inspection and winnowing. It is not a question of whether you will drink wine; it is only a question of whether it will prove a blessing or a curse.

History. The church has consistently used wine throughout history in the supper, and it is likely still the majority practice worldwide today. While we do not regard historical practice as absolutely normative, we do take it into serious consideration as an indication of how the Holy Spirit has led the church to understand how we are to apply scripture.

Practicals and precautions

For a church that offers grape juice today, I suggest that wine be offered as an additional option for those who are interested in taking it, so that both wine and grape juice are available and no one’s conscience is bound either way. For churches that pass out communion cups in trays, it would be possible to distinguish between the two either by the tint of the cups, by markings on the tray slots themselves (the inner rows are of one kind, the outer rows of another), or by passing several trays.

Certainly it must be a guiding principle for the church that “it is good not to eat meat or drink wine or do anything that causes your brother to stumble” (Rom. 14:21). There are several kinds of stumbling to consider:

- A brother who is prone to drunkenness may be tempted by the use of wine in the supper. This is a legitimate concern. For this brother it would be quite possible to continue to offer grape juice. However, it is also worth noting that this option has not been available throughout much of church history. It seems good to hope that many brothers in this position could be helped by being trained over time to drink wine rightly, connected with joy and fellowship rather than isolation and escape.

- A believer who is unaccustomed to the thought that Christians may lawfully drink wine, or that it is possible to drink wine without becoming drunk, may be severely distracted by the serving of wine. For churches in this situation, it would be pastorally necessary to provide education and time to reflect upon these ideas as a part of changing the church’s practice.

- However, a believer who remains prone to judge other believers who drink wine is not in view in Paul’s warning here. Such a believer is neither tempted to idolatry nor tempted to sin himself, but is rather passing judgment “on the servant of another” (Rom. 14) and is not walking “in step with the truth of the gospel” (Gal. 2). It is a kind of legalism or Judaizing to be confidently settled in our own practice and have scruples about how other believers behave, especially if it causes us to disdain, judge or withdraw from one another at the table (Rom. 14; 1 Cor. 10-11; Gal. 2). The introduction of wine in communion could actually provide a beneficial opportunity to a church to discuss how believers are to walk through disagreements over matters of practice, by highlighting the necessity not to pass judgment or to bind others’ consciences. This is always timely, because such issues are constantly cropping up in the church in diverse areas (education, nutrition, parenting, vaccination, entertainment, courtship, technology, etc.).

Conclusion

In determining how important the use of wine ought to be, we should consider just what kind of thing the supper is. Is it at root a visible-edible word-idea that primarily engages us at a rational-intellectual level? Or is it at root a covenant renewal meal that we sit down to eat together with Jesus in his very presence? This has a lot of implications, but as it relates to wine: do we really believe that we are seated together to dine with an extravagant king who calls us his friends? What kind of table do we believe that Jesus would set for his bride, or his bride for him? Does our practice tend towards reflecting all these beliefs and convictions?

Provided it is pursued carefully and wisely, I believe that a church can reintroduce the use of wine in communion in such a way that the whole church grows and benefits. Wine most appropriately shows forth and allows us to experience what Jesus intends to convey in seating and serving us at his table: including the richness and goodness of his creation and covenant, and his joy, merriment and prodigality toward us.

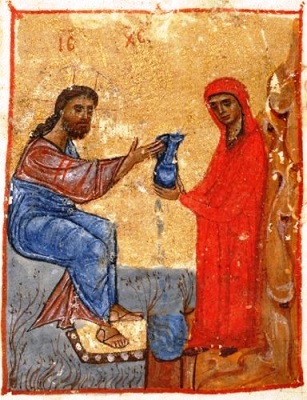

John 4

Some random questions and reflections on reading John 4, in no particular order and without having taken time to integrate them:

Some random questions and reflections on reading John 4, in no particular order and without having taken time to integrate them:

- Why does Jesus leave the area after the Pharisees hear? Do they function as a kind of Saul here, with Jesus carrying out the Messianic secret? Or could the Pharisees in this case be representing the quarrels over wells that took place in Genesis, so that Jesus is here repeating the paths of Abraham and Isaac in being forced to find another well? The latter seems appealing.

- Why Sychar? It is related to the Hebrew for beer and could suggest drunkenness. There seem to be mixed opinions on whether Sychar is Shechem. Contemporary Bible dictionaries seem to reject the idea. However, the connection with Joseph’s field (Genesis 48:22, and especially Joshua 24:32) seems to establish that this is Shechem. This is typologically very appealing, for in this passage Jesus offers the covenant to a non-Jew but he is not like the faithless Levi and Simeon whose offer of the covenant is only a pretext for murder. Levi and Simeon kill the men of Shechem after two days, but Jesus teaches the people of Shechem for two days.

- The sixth hour does not appear to have a strong Old Testament connection. I wonder here if it is rather serving a chiastic purpose, linking this passage with the sixth hour in John 19:14. Here, Jesus is named the Messiah; there, he is crowned. Here, Jesus speaks of his Father; there, of his mother. Both here and there Jesus thirsts. Both here and there women are prominent (the Samaritan woman, Jesus’s mother, Mary’s sister, and the two other Marys). Here Jesus speaks of the water he provides; there water literally flows from Jesus’s inner parts. Spirit and truth appear in both places as well. This fits with the chiasm proposed by Hajime Murai.

- The woman at the well is clearly marital imagery, following on two suggestions already in John that Jesus is the bridegroom, and following in the steps of the many wells in Genesis. The Samaritan woman is a new Hagar, Rebekah, Rachel, Zipporah. She is likely a type of Jesus’s bride, his church.

- Most commentators suggest that this Samaritan woman is a woman of poor character. James Jordan suggests that we have misread this, that she has simply been mistreated, following in the footsteps of the wives of Malachi 2 and Matthew 5 and 19. She is clearly no Jezebel. The fact that she represents a kind of typological Eve here I think tends to confirm this, that at worst she has been deceived and the primary blame lies upon her husbands. The fact that she may represent the church as the bride is a little less clear, as there are many more dimensions there (faithless shepherds, deceived flock, remannt). But I certainly don’t think she stands in for the faithless shepherds of Israel. Jordan’s suggestion seems very plausible.

- I have wondered often what it means to worship “in Spirit.” Some believe this implies the need for spontaneous emotion in one’s worship (perhaps connecting this with the wind of John 3 in order to reach this conclusion), but I don’t think that is what Jesus is getting at. James Jordan suggests that it implies “in the corporate meeting” because that is the sphere of operation of the Spirit, binding us together and working through us to minister to one another. That is possible, especially if we consider that this is contrasted against worshipping in Jerusalem. But I think the implication may be broader. Looking at Romans, being in the Spirit is identified with simply having the Spirit in you (Rom. 8:9ff), which is a consequence of belonging to and being connected to Jesus. This connection to Jesus is sealed in our baptism (Rom. 6), which ties us in to both the Spirit and the new creation kingdom (Tit. 3:5). That fits well with the preceding context here in John, which has much to do with baptism. So, we could paraphrase “in Spirit” by saying either “baptized” or “in the new kingdom-creation.” There is certainly also a Trinitarian aspect here: Father, Spirit, and Word-truth.

Essence and order

Related to my weekly communion jaunt, a friend asked whether I see communion as central to the liturgy, and what elements of the service ought to be present weekly.

As to which facet of corporate worship is central, I’m not sure we can identify that any more than we can identify which leg of a stool is central. I do see communion as the celebratory climax of the service, but no less important is Jesus himself speaking a word to his people through the mouths of his representative heralds (consider how it is that Jesus preaches peace to the Ephesians in 2:17).

The notion of worship as covenant renewal helps to answer the question of what is essential and even in what order these facets ought to appear. It is interesting that the New Testament portrays the church more as the new temple (2 Cor. 6:16, Eph. 2:21) and the new Zion-Jerusalem-assembly (Heb. 12) than the new synagogue. New covenant worship is the explicit heir of the old covenant’s sacrificial worship (Rom. 12:1, Heb. 13:10–16). We ought to look closely at how models like Sinai (consecration, word, meal with God) and the sacrificial system (the order of which is always purification offering, ascension & tribute, peace offering meal) translate into the new covenant. Other obvious covenant renewals like Deuteronomy and Ezra-Nehemiah are useful here; so too are David’s liturgical reforms that overlay sacrifice with song; and Revelation, however obscure, nevertheless gives us a heavenly pattern for organized corporate worship. Kline and others have done work analyzing the structure of Biblical covenants that is helpful here. But even considering only Sinai and the sacrificial system it seems evident that we ought to have a minimal pattern of confession-absolution; followed by ascension in song to bring tribute and hear a word from our commander-king-husband; and closing with a meal. (It seems possible to link these three legs of the stool with the offices of Jesus, and also with the members of the Trinity.) In addition to these three, a good case can be made as well for a kind of call and commissioning as opposite book-ends of the service.

How do we integrate this order of worship with 1 Cor. 14, where everyone is to bring a hymn, lesson, revelation, tongue, or interpretation? These fit with the central “ascension” portion of the service: the song and tithe and word. Obviously that leaves unanswered questions of what these things look like in detail, and what their specific place and proportion is.

Returning to the question of what is central in worship: it is Jesus who stands behind both word and food; worship is an actual going–up to meet with him. If he has spiritual eyes, who does the worship leader see when he turns around on the Lord’s day? It is Jesus (Rev. 1:10ff). Who is the true worship leader? It is Jesus (Heb. 2:12).

Weekly communion

Following is a series of blog posts arguing for the practice of weekly communion in the church. Weekly communion is not something for which we have an explicit command in scripture, so at best it is possible to establish it as a “good and necessary consequence” of scriptural examples and commands. This makes it a question of fittingness, betterness, and wisdom rather than a matter of right and wrong that ought to bind everyone’s conscience equally. Still, we ought to pursue not only what is permissible but also what is best, and I hope that you will consider with me the merits and blessings of celebrating weekly communion in the church. What follows is a set of arguments primarily from biblical theology and biblical typology: what you might call a sort of typological logic. I hope you will find these arguments to be cumulatively persuasive.

- In everything, eucharist!

- Jesus knocks: will we open the door and have a meal with him?

- Worship is sacrificial, so as priests we too have a daily partaking of bread and wine

- Worship is a tryst, thus morsels and wine

- Worship is the gathering of the host, a dress review banquet

- Worship is spiritual warfare, and we must always find a table set in the presence of enemies

- Tithing is linked with bread and wine via Abraham and Melchizedek, and is to result in “food in my house”

- Worship is not only a tryst, but a jealousy inspection, a day of the Lord

- Bread is to be set out continually in God’s house

- There is nothing better than to eat, drink, and be joyful

- Joyful feasting is commanded on the day of the Lord

- Following Moses’s inspired application, Sabbath feasting is how we obey the fourth commandment

- The church’s week to week experience ought to be a taste of God’s blessing rather than his judgment and withdrawal

- Whether or not we eat communion, we are showing forth something about the kind of table Jesus sets for his people

- Worship is covenant renewal, and to renew covenant is to feast

- Worship is in fact the renewal of a marriage covenant, and is it even necessary to ask how often a husband and wife should get together?

- Now that we have a perpetual sacrifice and are made permanently holy, we are continually in a festal season

- Worship ought to be accessible to all, from the least to the greatest

- The worship service that the early church inherited from the apostles was a Eucharistic service

- To enter God’s gates with thanksgiving is to enter them with a thanksgiving feast

- Not to eat together with the church worldwide is to fail to walk in step with the truth of the gospel

- The memorials of the Sabbath and the Supper are linked

- We must not grow weary of the table of Yahweh

- God is the kind of father who, if his son asks for bread, gives him bread

While Jesus may graciously overlook the fact that much of his church today does not practice weekly communion, we still ought to consider whether it is better for us not to practice weekly communion, and for this I think we have hardly any excuse. God could have chosen the ongoing renewal of his covenant to take many forms, and he chose to cast it as a meal, a covenant meal, a family meal, for very good reasons. It is a widely acknowledged truism even among unbelievers that families ought to to eat together as much as possible.

I hope you will find that this has not only brought to mind the merits of weekly communion, but also other applications. There are many additional worthwhile directions we could take our investigation, and perhaps your mind is already reaching towards some of them. For example, we could ask whether it is better to use wine or grape juice in communion; whether it is better to use bread or crackers; what is the most fitting portion size for communion celebration; whether communion should tend to a penitential or a celebratory tone (Deut. 14:26, Neh. 8:9-12); just what kind of self-examination the apostle Paul means for us to make; whether little children ought to have a place at Jesus’s table (Ex. 10:9-11); where communion ought to fall in the order of worship and whether it ought to carry the burden of confession and absolution; the appropriateness or impropriety of individuals’ withdrawing from the table; and what sort of passages might be appropriate for use in communion exhortation beyond the tried and true words of institution. Perhaps we will consider some of these in the future if time permits.