Archive for December 2025

Baptized

The Dutch nation, according to its origin and history, is a baptized, Protestant reformed nation; this Christian, Protestant, Reformed character of the nation should be respected and maintained.

The church should be recognized by the government as a divine institution which in its origin and existence is independent of the state. The government should protect the church in acting in accordance with Scripture and respect it in fulfilling the vocation assigned to it in Scripture. The government has the right to apply the truth, which the church professes, in its own field as it sees fit. (Hoedemaker, as quoted by James Wood, “How Abraham Kuyper Lost the Nation and Sidelined the Church”)

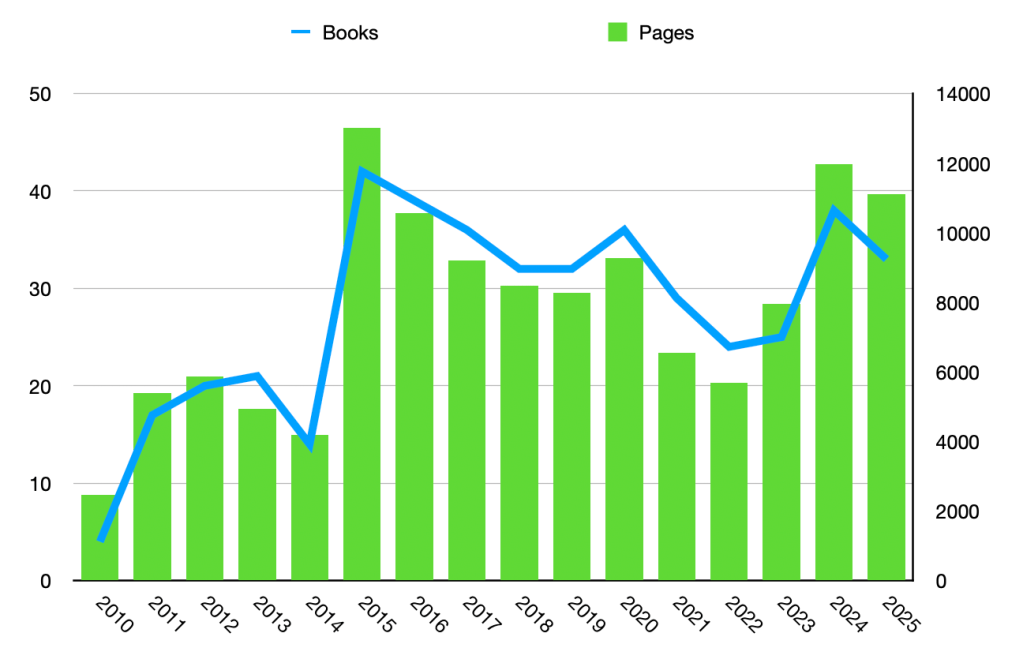

Years in books

I usually feel like I have little time to read, but my Goodreads “year in books” report at the end of every year consistently surprises me. In recent years I have increased my audio book consumption. This has redoubled in the last couple of years as I traded more podcast time for book time during my commute to work, and also as our family read-aloud time shifted toward audio book consumption.

I joined Goodreads in mid-2009. Here is my year in books summary since then:

Of the 33 books I read in 2025, 28 were audiobooks. Four of the books were re-reads (all of these were audiobooks). Six of my books were listen-alouds with the kids.

A complaint against the author

I recently finished reading C. S. Lewis’s book, Till We Have Faces. To the right is a cover illustration by Hannae Kim.

Till We Have Faces is widely acclaimed, and Lewis himself considered it to be “far and away my best book.” I was prepared to appreciate it greatly, but it fell a bit flat and felt a bit facile for me.

First, for a conversion story, it is surprisingly lacking in a sequence of obvious confession and repentance. Can we be sure that Orual has recognized all of her sins and failures?

Second, the most emotionally powerful portions of the second part—Orual’s being enabled to assist her sister in her travails—are watered down by having occurred only in dreams.

This is a specific example of a wider problem: the second part is rushed and didactic; it hardly has the character of story, has an unclear climax, and lacks the engaging nature of the first part.

While this story has great potential, much of this potential is dissipated by these weaknesses.

II

After some days’ reflection, I am compelled to confess my foolishness and retract my prior complaint.

The short nature of the second part is not necessarily a defect, nor is it lacking in story-like quality even though it is functioning as a different kind of narrative from the first part. This structure in fact mirrors the pattern of accusation, unmasking, and revelation that takes place at the end of a detective novel. We have been looking forward to being gathered with Poirot in the parlor for a very long time. There is a definitive climax and it is that accusation-revelation.

I am increasingly struck by the nature of the title and Orual’s corresponding statement, “How can they meet us face to face till we have faces?” By this Orual means that our innermost character, which we often keep hidden even from ourselves, is fully exposed. Orual’s complaint is her confesssion, because it is a compulsive vomiting of all of the ugliness and bitterness that she held inside. Her wearing a veil to cover her physical ugliness was a symbol of this greater masking; but ironically her obsession with her outer mask was part of how she hid from herself the existence of this greater mask.

Orual is physically unmasked and then unmasks her inner self, revealing “my real voice.” Her confession that “Yes,” she was answered is her repentance; she recognizes the thorough ugliness of it all. And this is the climax of the story.

But this is not a typical detective story; it is a Chestertonian one. The climactic revelation is followed by a second revelation. And this second revelation is not primarily that Orual’s dreams have a different meaning, but that her whole life is shot through with a different meaning.

The ways that Orual sacrificially helps her sister appear to occur entirely in dreams. But this does not necessarily mean that Orual is not actually suffering or giving of herself. In fact, since Orual’s life and strength are so suddenly and greatly weakened, it seems she is genuinely suffering through the course of these dreams. But in addition to this, Orual’s entire life has been consumed by a desire—selfish, but real—for the good of Psyche. In her confession and repentance, this desire is purified and, I suggest, Orual’s lifelong prayers are equally purified, and answered by the gods as such.

But it is also significant that the one real, non-dreamlike, active, and lifelong participation that Orual is revealed to have had in Psyche’s suffering was to serve as a harm, as an obstacle and temptation. The thought that Orual thus contributed to her sister’s maturation, purification, and sanctification does not seem immediately as beautiful or as emotionally powerful as the thought that Orual had helped her sister through other trials. But it is beautiful; a deeper, darker kind of beauty. What’s more, the reciprocal nature of this exchange, of this shared salvation, is more obvious than it is in the other exchanges—Psyche, in passing the test, herself becomes a means of Orual’s obtaining forgiveness and salvation.

If anyone intends the journey to Berea, let him bring this book for a traveling companion.

Unto repentance

I indeed baptize you with water unto repentance, but He who is coming after me is mightier than I, whose sandals I am not worthy to carry. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. (Matthew 3:11 NKJV)

First of all, I am not a language scholar and I hesitate to make much of a preposition.

Second, John’s baptism is not the same thing as Trinitarian baptism, so we should hesitate to make straight-line applications from John to Jesus and his church. In a manner of speaking, John was bringing faithful covenant people back to life after their having come into contact with death. By contrast, Jesus by baptism brings people into his covenant for the first time, bringing them to life once and for all.

Nevertheless, the idea of a baptism being unto or toward repentance is significant. Rather than baptism being, as Robert Stein would have it, a mere synecdoche for a faith-repentance-baptism sequence, this shows that baptism is in fact a performance of repentance. Just as James teaches us that faith must be performed in order to be fully realized, so too repentance must be performed in order to be fully realized.

This by itself is not proof of paedobaptism, though it is highly consistent with paedobaptism and paedofaith. But it is proof against a facile credobaptism: if you require someone to repent before their baptism, you are in a sense requiring the impossible.