Edward

Sources:

- Waalwijk Wiki, Eduardus Constantinus Josephus Moonen, via the Internet Archive

- Waalwijk Wiki, Oorlogsmonument, via the Internet Archive

- Google Translate

Eduardus Constantinus Josephus Moonen

Eduardus Constantinus Josephus Moonen (Strijp, 24 June 1876 – Waalwijk, 6 September 1944) was married to Henriëtte Antonette Christine Sassen. He was mayor of Waalwijk from 1 March 1924 (Royal Decree 12 February 1924, no. 12) to 1 February 1944 and then acting mayor from 19 May 1944 to 6 September 1944. From 1924 to 1933 he was also deputy district judge.

Mayor

Moonen started his career in 1901 as a second lieutenant of the infantry and ended his military career as captain-adjutant in Breda. From this rank he was appointed mayor of Waalwijk quite unexpectedly. He was 48 years old at the time.

At the inauguration Moonen spoke the following words, in which he made his policy known: ‘It is entirely in line with my aim to be a good mayor for everyone, without exception for the entire population of Waalwijk’ and ‘from that source I will draw the strength to remain true to the motto that I want to make mine, even under difficult circumstances: everything for everyone.’

He became the binding force that tried to give shape to the trinity of the places that were merged in 1922. An expression of this was the way in which his twelve and a half years as mayor were celebrated. The entire population of Waalwijk, associations and institutions from Baardwijk, Waalwijk and Besoijen were present to honor their mayor.

Moonen’s term of office was characterised by more lows than highs. High unemployment, especially in the shoe and leather industry, caused the municipality concern. Support schemes were introduced. The shoe law brought some relief. The housing shortage increased and there were many slum dwellings. A development plan was drawn up for the area between Grotestraat and the railway line. The St. Crispijnstraat and surroundings were constructed, as well as the Besoijensche Steeg. The backlog of public facilities in Baardwijk was tackled. A public slaughterhouse was established. The harbor plans were continued and through Moonen’s persuasiveness the construction of the new town hall was assigned to Kropholler and carried out.

That he wanted to live up to his inauguration speech became apparent at the farewell of an alderman in 1926, when he pointed out the attitude that council members should have, namely to subordinate their own interests to the municipal interest. Genuine civic spirit, he stated, is the only basis on which an impartial treatment of public affairs can and may be based. Apparently other views existed during his term of office. For him, ‘omnibus idem’ (the same for everyone) applied.

As of 15 April 1924, Moonen was appointed deputy district judge. As a result of the abolition of the Waalwijk district court, he was honourably discharged from this office as of 1 January 1934.

He was faced with major decisions of conscience, he could no longer rely on the council, during the war years in the implementation of the measures imposed by the occupier. When Moonen retired in February 1944, he was called upon to take up the office again a few months later, as his deputies (the aldermen) were not available due to illness and busy work, and an NSB member apparently no longer wanted to come to the fore at that time.

On 6 September he died before the firing squad of Dutch SS members. His honorable discharge granted to him by the occupier in February 1944 was converted into an honorable discharge from K.B.

War victim

Mayor Moonen got up early on Wednesday, September 6, 1944. Like most people, he wondered where the liberators were; the reports about their advance were rather contradictory. He walked up and down in front of the town hall and accosted two resistance fighters who unfortunately knew just as little as he did. Around nine o’clock, Moonen entered the town hall, followed shortly afterwards by two women who wanted to talk to him. The tragedy had begun.

The previous day, a number of NSB members and Landwachters had been arrested. One woman was married, the other engaged to a Landwachter. They were naturally very worried about the two men. After all, they had also heard the stories about what would happen to the ‘traitors’ and they feared the worst. They turned to Mayor Moonen, but he could not help them any further (the two had been locked up in Sprang together with ten others). Disappointed, the women walked outside again. It was now half past nine.

Camouflaged vehicles drove into Waalwijk. It was the vanguard of the Landstorm Nederland. This battalion of Dutch SS men, the cadre of which was largely German, was on its way to the front near Antwerp. The SS men were in a grim mood. Furious about the flags they had seen on the way, they had shot at a crowd in Vlijmen and in doing so had killed three people, including a boy of barely seven.

In Waalwijk too, flags were hanging everywhere and the SS men stopped at the town hall to have them removed. That’s when the two women stepped outside. They accosted the first Dutch officer they saw and told their story. The SS man promised to help them. He stormed into the mayor’s office with his pistol drawn and demanded that the flags be taken inside and the two men returned to their wives. Moonen could do something about the first, but not about the second. The Dutch officer waited a while until most of the flags had been taken inside and then wanted to drive away again, because he also saw that the mayor had nothing to do with the kidnapping. At that moment his superior, Hauptsturmführer Maasz, arrived. The women also complained to him.

Maasz had a completely different character than his colleague. He was a typical arrogant Nazi for whom a human life was worth little. A few days earlier, he had had a soldier shot dead because he had stolen some petrol. He promised the women that he would wash the pig (i.e., do the job quickly). He approached Moonen, who had come outside and demanded the return of the land guards. He waved away protests: Moonen was mayor after all, he should know where the two were. He gave Moonen half an hour to find the men. The mayor went inside and called the leader of the Waalwijk OD for advice. But he did not know where the land guards were either.

Maasz’s patience was running out. He asked the women if they knew anything more about the kidnapping. ‘Yes,’ said one of them, ‘there was also a boy from Hoffmans there.’ The SS men then went to the house of the Hoffmans family, which had been pointed out by the women. There they dragged the 25-year-old Vincent and his 18-year-old brother Joop out of the house. Unfortunately, the women had been wrong. A cousin of the two brothers was involved in the kidnapping, but the brothers were completely innocent and did not know where the land guards were. Maasz did not care. He put the boys and the mayor under the lantern in the middle of the Raadhuisplein. It was now half past eleven. Maasz gave an ultimatum: he would wait until one o’clock, then the missing land guards had to be back. If not, the three would be shot dead.

Half an hour later, the SS men started to make preparations for the execution, presumably to scare the three men. Vincent now really got anxious and told the SS men that he had heard that the kidnapped men were somewhere in the municipality of Sprang-Capelle; he did not know where. Maasz sent a car, with Vincent as a guide, to Sprang. After half an hour, the car returned to Waalwijk empty-handed. Then a fourth person had to stand under the lantern, doctor Piet Lenglet. Lenglet had heard from an agent that the land guards might be released and he passed the message on to Maasz. When nothing happened, Maasz wanted to know from whom he had heard it. Lenglet did not want to betray his source and as punishment he was put with the others. It was about a quarter to one.

The clock ticked on relentlessly. The autumn sun beat down mercilessly on the heads of the four waiting men: doctor Lenglet, his face contorted with fear; Vincent Hoffmans, seemingly unmoved; his brother Joop with his hands hanging listlessly at his sides and mayor Moonen, the former officer, standing upright and with his head held high. The ultimatum had expired, but apparently Maasz was not happy either, because the time passed without anything happening. Mayor Moonen again pleaded for the three others. He pointed out that doctor Lenglet, as leader of a Red Cross team, was protected by international law. Maasz finally gave in and let Lenglet go. It was a quarter past one.

Maasz’s patience was now really at an end. Once again, after much insistence from Moonen, a priest was allowed to join them. Dean Heezemans tried to encourage the three condemned to death. Joop, the youngest, in particular, had a hard time. He tried to hold on to the priest. Then the dreaded order sounded: ‘Go ahead, it’s time.’

Because Mayor Moonen’s wife could follow everything from the window of the house on Raadhuisplein, Moonen asked as a last favor to have the execution take place behind the town hall. Maasz agreed. Together with two Dutch SS men, he accompanied the three men to the place of execution. The three Waalwijkers had to stand next to each other, facing the wall of the town hall. The two SS men picked up their weapons. Then Maasz shouted: ‘Feuer’ and the machine pistols crackled. It was exactly seven minutes past half past one.

The two non-commissioned officers turned out to be poor marksmen and only after a coup de grace were the mayor and Joop dead. Vincent miraculously survived the execution and the coup de grace. While dean Heezemans, who had seen that the coup de grace missed its target, distracted the SS men, he managed to scramble to his feet and run away. He was picked up and taken to ‘s-Hertogenbosch where an operation ultimately saved his life.

Oorlogsmonument (war monument)

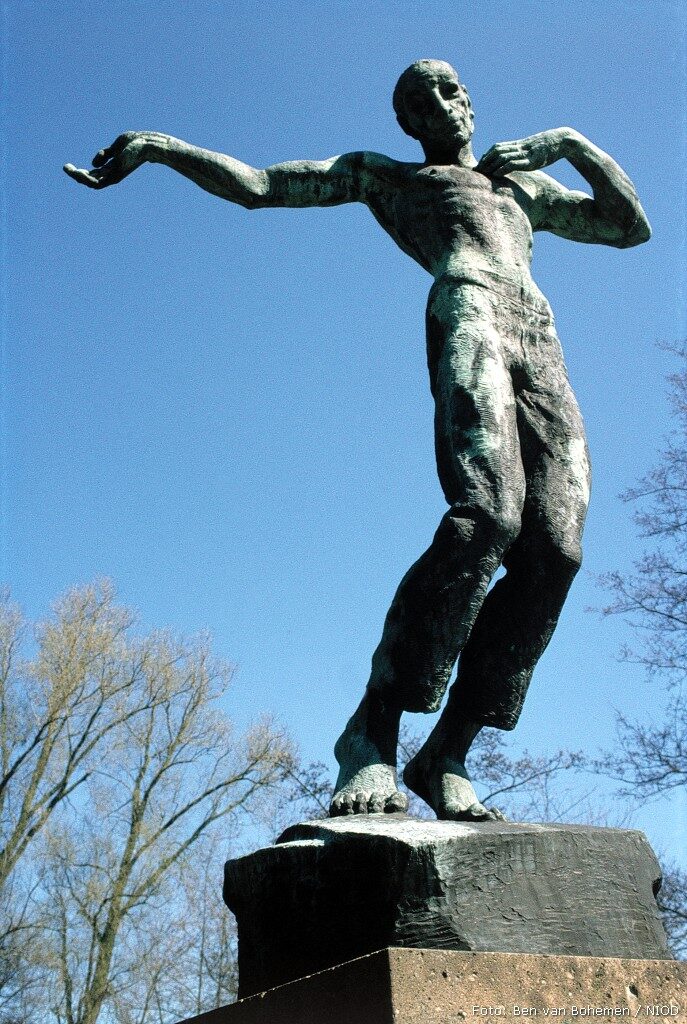

The War Memorial on Burg. Moonenlaan is a monument in memory of all Waalwijkers who died during the occupation and in particular of mayor Moonen, who was shot by the occupiers during the war. On October 30, 1949, the monument was unveiled by Mrs. H.A.C. Moonen-Sassen (1876-1957).

The commemoration takes place at the monument every year on 4 May.

Design

The monument, made by the Binder company from Haarlem, was designed by J.A. Raedecker. It is a statue of a male figure, collapsing after a firing squad. G.H. Holt designed the substructure and entourage.

Execution

The pedestal bears the dates ‘1940-1945’, the names of the Waalwijk war victims are engraved in the hard stone slabs that are placed around this pedestal, as well as a poem by Mrs. H. de Kat-van Zijl:

THEY FELL TO EARTH BEFORE THE GLOWING OF THE GOLDEN SUN,

FREEDOM DROVE AWAY THE LONG NIGHT OF WAR, FOR US, SPARED.

A MORE BEAUTIFUL MORNING SURROUNDED THEM, FALLEN TO HEAVENLY GARDEN,

WITH THE LIFE GIVEN TO THE BROTHERS, WOVEN FROM ETERNAL JOY.

The statue of cast bronze is 2.75 meters high. It stands on a 2-metre-high limestone column, which measures 1 x 1 meter at the top. The 4 x 4 meter pedestal is made of limestone with plates of bluestone. Bluestone boulders have been placed around the monument in a circle with a diameter of 16 m.

Special features

In 1965, art critic Pierre Janssen described the deeper meaning of this monument in the book ‘Two minutes is it quiet,’ referring to the gruesome and senseless execution by the Germans of mayor Moonen and Joop Hoffmans on 6 September 1944, with the following words:

Then they were captured and one day their lives suddenly ended. The man is just barely standing. But he will fall in a moment. Just look at his feet and his knees. Look, he is very lonely. He’s not angry. He does not resist anymore. He stretches out his arms and gives away his life. Just look at his face. It is a calm face. He sacrifices himself. This statue is there to help us remember that freedom is precious. A lot has been paid for it. Not with money, but with human lives.

Immediately after the liberation, De Echo van het Zuiden started collecting funds for the erection of a monument. Later, at the suggestion of the Waalwijks Belang association, it was decided that it should be a statue that would keep alive the memory of all Waalwijkers who died during the occupation.

The Waalwijk war monument was depicted on a postage stamp in 1965.

Raedecker is also the designer of the statues that are part of the National Monument on Dam Square in Amsterdam.

Leave a comment